Passage 6: Stages of Change: Why readiness isn’t willpower

If productivity were the measure of readiness, I’d be fine.

I can produce. I can teach. I can create. I can deliver. You’re probably not surprised; you may have even watched me do it.

But put a simple life-logistics task in front of me—sign the estate documents, open the mail, handle the thing that makes adulthood obligations feel real—and suddenly I lose traction. My competence doesn’t translate.

It’s not because I don’t know how. And it’s not because I don’t care. It’s because when I sit down to do it, my body changes the subject.

Light

Dark

My attention skitters. I shift focus. I remember six things that are easier to finish (even if they’re the very things someone else can’t start). And when I tell myself that I can do it later, I feel the smallest wash of relief—like I’ve stepped back from the edge.

And that relief is the tell.

Relief doesn’t show up when something is merely inconvenient. It shows up when you’ve just avoided something your body is registering as costly—emotionally, symbolically, or physiologically.

Which means there’s a good reason I can produce all day and still avoid a signature.

There’s always a why.

And for me, the why isn’t difficulty—it’s meaning. Somehow, those tasks land as threat. Not bear-in-the-woods threat. But the quieter kind, made of responsibility and consequence.

Because these efforts I dodge aren’t just projects to complete. Estate planning, as an example, isn’t just paperwork—it’s encountering the unglamorous truth that I’m the solo adult holding this thread in my little family. It asks a question I don’t get to outsource: what happens when I’m not here to take ownership? (And if you’ve ever wondered why an older parent won’t sign the forms, discuss the downsize, or talk about “after”—it may not be stubbornness. It may be self-protection. Paperwork can feel like a forced rehearsal.)

Years ago, my first business coach took me to a money mindset conference. She believed my work could change the way we do healthcare—but only if I moved beyond meaning and impact alone. During one session, they divided the room into four groups—spenders, savers, monks, and avoiders. After a behavioral questionnaire, I joined the “avoiders” at the back of the hall.

We were maybe thirty people, dwarfed by the swarms of spenders and savers on either side of the room. Our assignment was to name the self-prompts that would interrupt our pattern of avoidance when at home. A man behind me said, simply: “Open the mail.”

We all burst into laughter—not because it was funny, but because it was true. It was the kind of laughter that’s half confession, half recognition. For an avoider, opening the mail isn’t administrative. It’s exposure. Exposure to duty—and the consequences that can feel too huge to hold all at once.

And when something feels that big, readiness matters more than willpower.

In other words: what looks like “I should be able to” is often a flow problem: the next step is asking for more than the current stage can support.

The problem isn’t discipline at all, but a stage mismatch.

““The most successful interventions are those that meet people where they are, not where we think they should be.””

Fit before force

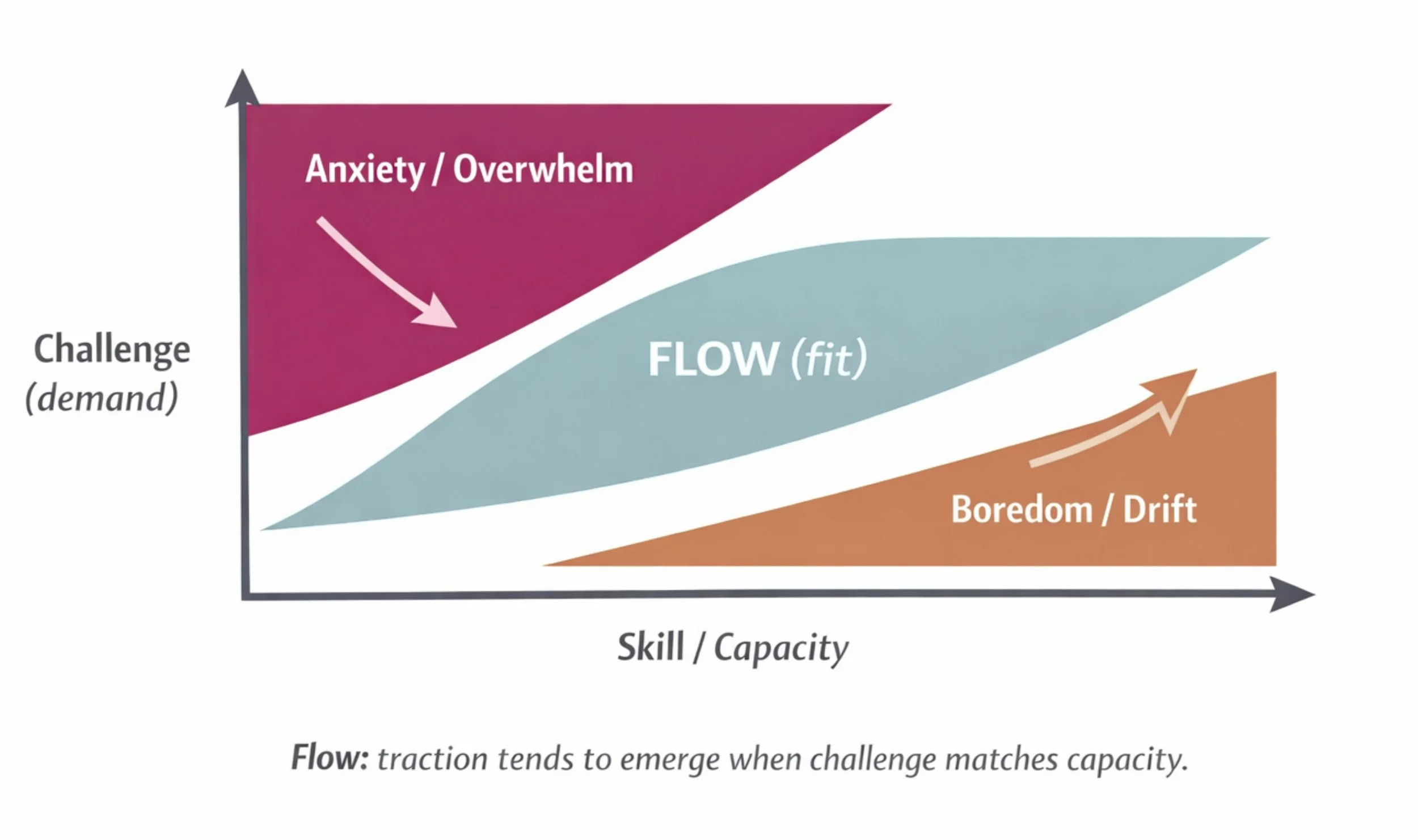

This is where Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s “flow” model helps as a visual: When the challenge of a step matches the skill and capacity available, we get traction. When the challenge overshoots capacity, we don’t get negligence—we get overwhelm and avoidance. And when it undershoots, we get drift or boredom.

In other words: flow isn’t willpower. It’s fit.

I’ve spent the last 20 years watching what people say they want collide with what their bodies and lives can actually hold.

Since 2009, I’ve worked as a Functional Medicine Nutritionist and educator, looking for the root causes (what’s underneath the symptoms)—and watching what actually makes change possible in real bodies and real lives. Since that time, I’ve heard people tell me—sometimes in their very first sentence—that they want “the plan.”

Just tell me what to eat.

Tell me what to cut.

Tell me what supplements to take.

Give me the protocol.

Give me the rules so I can be “good.”

And I understand the hunger for clear instruction. When you’ve been sick, confused, dismissed, or living with symptoms that don’t make sense, rules can feel like reprieve. A regime can sound like a handrail back to normalcy. Structure can masquerade as safety, hope, and promise.

Over time, my understanding of change has transformed —because I’ve seen how often the “right plan” becomes the wrong demand at the wrong time. I’ve witnessed the same thing happen repeatedly: the desire is real, but life load is not ready. That isn’t a measure of virtue or compliance. It’s a measure of capacity.

If you’re not sleeping, your blood sugar is swinging, your stress load is already high, your pain is constant, your inflammation is humming, you’re carrying a lot in life right now, and your stress response is running hot—then asking your body to “just comply” with a strict plan or protocol is like asking a person who’s under water to recite a poem.

We also need to consider the world around the body: sleep is shaped by shift work and caregiving, food by budget and access, readiness by safety and lived stress. Capacity isn’t just personal—it’s structural.

Most well-intentioned protocols are written for people with slack in the system—time, money, support, bandwidth. They assume capacity for forward momentum when many people are living in some form of survival.

And here’s the uncomfortable truth: protocols aren’t scarce. Context is. You can find “what to do” in five minutes online. What you can’t find in a book or blog post is whether your body and life can hold it—today. Fit creates traction. Force creates fallout.

““The belief in the ‘magic bullet’ leaves only one, defeating conclusion when success is not immediate: that you are not doing enough and must do more of the same.” ”

This is why stage mismatch—capacity vs. demand—can wreck even the best plan. If you’ve been there, you haven’t messed up. The ask is just bigger than your bandwidth. We go all-in—fasting windows, eliminations, workouts, a supplement schedule that needs a spreadsheet—and our bodies push back, not from weakness, but from being already maxed out.

Let me offer a few composite scenes from practice—details changed, patterns intact—so you can see what stage mismatch might look like in the field:

The single mom who wants a healthy family meal plan—but she’s parenting and working on five hours of sleep, running on cortisol and caffeine. By day four, the prep collapses, and she calls it failure instead of depletion.

The college student who wants to quit sugar “for her skin,” but she’s underfed on a cafeteria routine that’s low in protein and minerals. Then 11 p.m. hits, cravings spike, and she calls it a lack of discipline instead of biology.

The 50-year-old who wants to start lifting weights to strengthen their bones, but they’re inflamed, drained, and in pain. They push through, flare, and decide their body is betraying them—when it’s signaling that capacity hasn’t caught up to demand.

Across all three, the pattern is the same: the plan they were given may not be wrong—the timing is. Capacity is already spoken for, and the prescription requires more bandwidth than they have available.

““The belief in the ‘magic bullet’ leaves only one, defeating conclusion when success is not immediate: that you are not doing enough and must do more of the same.””

The story that misdiagnoses people

Culture then arrives to pile on.

It doesn’t interpret the stumble as information. It reads it as evidence.

We live inside a moral frame that treats change like a performance: if you really wanted it, you would ‘just do it’. If it’s not happening, you must not want it enough. You must be undisciplined. You must be doing it wrong.

That story doesn’t just shame people—it misdiagnoses them. It takes a physiological, psychological, or sociological signal and treats it like it’s an indication of a character flaw.

And here’s the part I have to own too: I’m not immune to the seduction of “trying harder.”

I grew up in a world—clinically, culturally, and personally—where effort was an ethic, excellence was everything, and enough was elusive. Where powering through was praised. Where doing more felt like being more.

So when someone couldn’t follow the plan, the reflex was to tighten the rules. Add accountability. Increase follow-through.

But the longer I’ve done this work, the more convinced I am: when the body won’t do the thing, it’s rarely a problem of resolve. It’s a stage problem—capacity before compliance. And eventually, I realized I needed a map for this—something that could name readiness without blaming the person (myself included).

Society loves a clean narrative: decide, act, transform. Yet most of us are attempting change inside crowded lives and complicated bodies—medical trauma, chronic stress, unstable schedules, thin support, invisible grief. So when the plan collapses, the moral frame steps in and calls it a character problem. And we often adopt that perspective. The stages offer a different lens: not “what’s wrong with me?” but “what stage am I really in—and what’s an appropriate next step from here?”

Naming your stage isn’t procrastination—it’s how you restore flow: right-sized steps, taken on purpose.

“This compassionate pivot is simple: What stage am I in—really?”

The reframe: change is staged, and context matters

There’s a behavior-change model I reach for a lot in my work: the stages of change.

I don’t believe human transformation can be reduced to a neat staircase, but I do think readiness is real. This model gives language to a pattern we all live: we move in phases.

The model was first developed in studies on smoking cessation, but its insights translate far beyond cigarettes.

Change isn’t one decision. It’s a process. Often a looping one.

Somewhere between “I’m not doing this” and “I’m doing this!” there are recognizable thresholds:

not ready to look yet

ready to admit what’s true

ready to imagine a different way

ready to plan

ready to act

ready to keep going

ready to begin again after a slip

ready for the new thing to feel normal

Even naming those thresholds can be comforting—because it contradicts the cultural script that says: If you wanted it, you’d do it.

Here’s my added translation, the one I care about most:

Readiness isn’t identity.

It isn’t a character strength, and it isn’t righteous.

Readiness is capacity meeting demand.

Sometimes the mismatch between capacity and demand is physiological—the difference between “I can” and “I can’t today.” Sleep. Blood sugar stability. Pain. Inflammation. Nutrient sufficiency. Nervous system state.

Examples of “I can’t today” may include:

Adding bioidentical hormones to a body that can’t clear what it already has—because bile flow is sluggish, constipation is chronic, or the liver is overburdened. Then “support” can feel more like side effects.

Pushing detoxification protocols on a body that isn’t moving waste—no daily bowel movement, poor sweating, depleted minerals—won’t bring relief. It will likely yield reactivity. You could call it “retox,” but it’s really just: the exits aren’t open.

Trying to “fix” sleep with more tools and supplements while blood sugar is crashing at 2 a.m.—and the nervous system keeps doing what it’s designed to do: wake you up.

Sometimes the mismatch between capacity and demand is situational—bandwidth, childcare, safety, money, food access, work schedules, social support, medical trauma, the chronic stress of living in a world that asks too much and gives too little.

Examples of “my life isn’t ready” may include:

You’re asked to “avoid inflammatory foods” and “cook more at home”—when you’re relying on whatever is fastest and affordable—and you won’t get the nourishment you’re after. You’ll likely get more shame and fewer whole foods.

You read that you should “advocate for yourself” with a new provider—when you’ve previously been dismissed, humiliated, or retraumatized in exam rooms—and you likely won’t feel empowered. You’ll experience more of a freeze response dressed up as procrastination.

Receive a request for food tracking by a clinician looking for insight—and if your food history is neutral, you may collect data for patterns. But if your history includes restrictive dieting or disordered eating, you might experience panic and activation instead of delivering testimony.

And sometimes the mismatch between capacity and demand is the meaning of the ask itself. The task is no big deal, but what it represents is sizable—mortality, responsibility, growing up, a line you cross where things become real.

The part most perspectives on change don’t emphasize enough is this: change is not only behavioral. It’s relational. It’s symbolic. And it’s shaped by the world and body you live in.

And culture keeps trying to turn that complexity into a conclusion.

“The myth goes like this: decide → act → transform.”

A crisp before-and-after. A hero montage. A clean reveal. A new year’s resolution.

But real change rarely looks like that. Real change looks more like: stumble → stabilize → resist → return.

And if you’ve ever been in a body that’s scared, depleted, inflamed, under-resourced, or carrying grief—you know that the initial wobble isn’t weakness. It’s information. It's the inner council negotiating cost, conserving resources, trying not to break.

Which brings me back to the question I want to explore in this Passage:

What if we’re not failing, but instead asking too much of ourselves from the stage we’re in?

In the earlier Passages, I’ve been circling transitions: the endings, the in-between, the liminal space, the load we carry when life is asking us to become someone new. That work matters because it tells the truth about why “just do it” so often misses when we enter a transitional phase.

But after you name the liminal space, the next question is practical—and likely tender:

What can I do from right here, without turning myself into the enemy?

And here’s something the stages model gets right, even if it’s imperfect: We’re not one stage.

We’re a mosaic.

You can be in the Action Stage in one domain and in the Precontemplation Stage in another. You can build a business, raise a family, show up for everyone else—and still struggle when the task confronts your mortality, like executing your Will. You can be “ready” in the places that earn applause, and “not ready” in the areas that don’t. Or the reverse: you might be able to face mortality on paper, and still be in precontemplation about strength training, bedtime, or the daily rhythm your body craves.

That doesn’t make you inconsistent. It makes you human.

““Completing the tasks in each stage of change is often not linear. There is often a cycling back to (or a ‘recycling’ through) earlier tasks.””

And it tells you something else, too: the point isn’t to shame the stage you’re in. The purpose of identifying the stages is to work with them. To stop treating readiness like a moral accomplishment. To stop confusing effort with worth. And to stop calling it a failure when it’s often a capacity mismatch.

If we lean into a model like Stages of Change, we can ask questions of orientation:

What stage am I in with this one thing I am attempting?

What would make the next step viable?

What would count as progress that doesn’t ruin my week?

While we live in a culture obsessed with speed—protocols, regimes, quick fixes—what I’m trying to practice (and invite) is something slower and more honest:

change that respects your timing

change that respects your body

change that respects your life

““You have to live in the situation you’re in, and not the situation you want to be in. And I think acceptance is one of the hardest things that people can do.””

Before we walk through the stages, one clarification I need to emphasize: recognizing your stage isn’t a delay tactic. It’s what prevents the most common mistake—trying to leap when what you actually need is a gentle runway.

The stages as lived experience

I want to make the Stages of Change as straightforward and usable as possible—less a model, more a mirror. A way to locate yourself without turning the moment into an indictment. A way to say: This is where I am. This is my starting point.

And then we can ask the only question that matters: What would help from here?

One reason this framework has stayed useful for me is that it aligns with what I’ve seen in real people: change rarely comes from a single, unified decision-maker. It comes from the inner council: The part of you that wants relief shows up to the meeting. But so does the part that’s exhausted. The part that’s afraid of consequences. The part that’s loyal to the way things have been. The part that’s tired of “trying.”

You don’t need to be broken to feel divided. You just need to be human.

That’s why readiness can look so “irrational” from the outside. You can mean it—and still not move. You can want it—and still circle. You can take one step forward, then find yourself right back where you started. This isn’t a deficit. It’s a normal nervous system negotiating cost—and that negotiation is part of how stages work.

And yes—people argue about whether or not human change fits cleanly into the stages we’ll explore. That’s fair. Bodies don’t love tidy categories, and life doesn’t move in straight lines. Still, this map provides a decent compass. It helps you see the difference between pressure and readiness, between a plan and latitude, between what you “should” do and what you can actually realize.

So I’m going to walk through the stages the way I think about them in practice: as lived experience. As a way to take your place on the map, and an invitation to stop critiquing where you are and start working with it.

Stage 1: Precontemplation — “Not yet. Not now.”

In this stage, the change sits outside your field of vision. You forget. You avoid. You tell yourself you’re fine, or that you’ll handle it later. You scroll past the article. You let the voicemail sit. You keep the envelope or supplement bottle unopened on the counter, as if it were ornamental.

On the inside, it doesn’t feel like defiance. It often feels like nothing. Or it feels like fatigue or a quiet “no” that offers zero explanation.

Your body is doing something here. And your brain is saving energy by avoiding engagement with what might demand more than you can give right now. Some may call that denial, but it’s often closer to protection: the mind conserving energy by avoiding what might demand more than you can give right now.

““Change is hardest when you don’t yet believe you need it.” ”

In last week’s Passage we explored The Window of Tolerance. That helps us name your current state—how activated you are, how much you can adapt right now. Stages of Change helps us name your position in the process—what kind of step is appropriate from here, often influenced by your state.

And Stage 1, precontemplation, has many disguises: a shrug, a fight, a collapse, a blind eye, a perfectly reasonable argument. In all of them, the same internal vote wins: not now.

Culture will often respond with a shove during precontemplation. A parent sees their teen dismiss a conversation about grades, driving, therapy, work—whatever the “serious thing” is. The parent leans in harder. They lecture, threaten, list consequences, raise the volume. The teen looks blank or irritated and says, “I don’t care.” What the parent experiences as indifference may be overwhelm. What looks like an attitude may be a pull inward. The more the parent pushes urgency, the more the teen slams the door to stay safe.

Or in a clinical setting, a practitioner orders a test and uses it like a scare tactic—hoping the data will finally “wake someone up.” An alarming lab marker, a scan, a risk score. The message lands as: You should be afraid and do something about it. For some people, fear creates action. For others, fear creates freeze. They leave the appointment flooded, then do the most human thing imaginable: they avoid the portal, avoid the follow-up, avoid the plan. Or they sprint—book the appointments, buy the supplements, do the overhaul—then may hit a wall and vanish. Either way, the result gets labeled “noncompliance,” when it’s often a human being preserving themselves from too much, too fast.

““Contrary to some people’s approach, giving your client a shove in the back is probably not a good idea. That first step has to come from within.””

In Stage 1, “more pressure” may look like care from the person offering it.

But it feels like danger from inside the recipient.

In precontemplation, we haven’t reached full-body consent to the idea or recommendation—only a mental understanding that it’s “a good idea,” at best.

What helps here is not a push—it’s a little safety. This stage responds well to options, not ultimatums. A small moment of contact that doesn’t spike the alarm. A humane request for one honest sentence. “When I think about this, my body feels ____.”

That noticing counts. It’s connection without overwhelm—and that’s how change begins.

You’re probably in Precontemplation when:

you keep “meaning to” and somehow never start

you feel oddly blank when the topic comes up

you get a tiny wave of relief the moment you decide to do it later

This stage responds to safety, not urgency.

Stage 2: Contemplation — “I know… and I don’t.”

In this stage, the change enters your awareness—but it doesn’t have you convinced just yet. You research. You gather information. You save the post. You listen to the podcast while walking. You ask good questions. You make a mental plan. You imagine yourself doing the plan. You might even buy the book, the tracker, and the new water bottle for your new life. You join the gym or sign up for the subscription.

On the inside, it can feel like living in two truths at once.

One part of you wants reprieve—another part of you braces for the cost. You say “I should” a lot. You tell yourself you’re “working on it.” And you very well may be. You may also be circling the shoreline, staying close enough to feel hope—far enough to avoid consequence.

““Conducting a risk-reward analysis and deciding to act are central tasks of the contemplation stage.””

You’re running a risk-reward analysis in the background. And ambivalence takes energy. It keeps you scanning, evaluating, and running scenarios. The mind returns to the question again and again: Is this safe? Is this worth it? Can I afford the fallout if I fail? And even when you’re not in motion, your stress chemistry can stay quietly engaged—tired and wired, mentally busy, emotionally stuck.

Contemplation has its own disguises: “I’m just learning,” “I’m waiting until things calm down,” “I need the right plan,” “I’ll start Monday.” In all of them, the internal vote splits: yes… and not yet.

Our culture loves this stage. It monetizes it!

It sells you promises and calls it empowerment. It offers more tools, more protocols, more perfect routines, more “What you’re doing wrong,” and it keeps the answer one purchase away. Contemplation becomes the waiting room you start to furnish.

“Our culture loves to monetize the Contemplation Phase with promises and products.”

You can see it at the kitchen table. Someone keeps bookmarking recipes and reading about blood sugar balance, while eating the same meal night after night. They’re not lazy. They’re negotiating with reality: time, budget, kids, exhaustion, a partner who isn’t on board, a body that’s already carrying too much.

The desire is sincere. The scaffolding isn’t there yet.

I’ve heard a version of this repeatedly over the years: A person finally feels seen, finally has a name for what’s been happening in their body, finally gets a plan that sounds like hope—and they leave the appointment full of intention. Then the week arrives. The plan asks for food prep, schedule changes, symptom tracking, appointments, supplement timing, and a whole new way of living inside a life that’s already maxed out. They don’t refuse. They stall. They “get organized.” They keep meaning to start. That isn’t sabotage. It’s the reality of needing a smaller first step.

In Stage 2, the temptation is to confuse thinking with moving; desire with readiness.

What helps here is not the grand gestures—it’s a gentle decision. Think basecamp, not summit. Choose the step your life can repeat. Something small enough to be real. Name the cost of staying the same, then choose one 10% shift your life can actually hold before moving on. One appointment made. One breakfast upgraded. One text to the friend who steadies you. One boundary that gives your day a little more room. One move that turns contemplation into progress.

And to be clear: 10% isn’t universal. It’s not a moral unit. It’s a capacity unit. What counts as “small” depends on what you’re already carrying—and what’s already working.

Choose heal over ideal: embrace what supports your capacity, not what matches the “perfect” plan.

If you already sleep through the night, a slight shift in your fasting window might be doable. If you’re waking at 2 a.m. with adrenaline, your 10% might be a protein-forward dinner or a bedtime snack that keeps blood sugar from dropping.

If you already take supplements without it turning into a project, a single targeted addition might be a valid 10%. If pills already feel like pressure, your 10% might be putting them where you can see them—or pausing everything new until breakfast is steady.

If your bowel movements are regular, adding fiber or bitters may be helpful. If you’re constipated, your 10% might be hydration, the appropriate form of magnesium, or simply getting one “exit” open before asking the body to process more.

If your mornings have any slack, your 10% might be a real breakfast. If mornings are triage, your 10% might be stocking two “good-enough” options you can grab without thinking.

If tracking food feels neutral, a week of notes can give helpful insight. If tracking lights up old wiring, your 10% might be tracking one data point—energy after meals, cravings at night, stool frequency—without logging a single bite.

You get the idea. Ten percent is whatever you can repeat without rebound—and that looks different in every body and every life. The right 10% doesn’t make you heroic. It makes you consistent.

You’re probably in the Contemplation Stage when:

you consume a lot of information, but nothing changes on the ground

you keep saying “I should,” and feel both hope and dread in the same breath

you’re waiting for certainty, energy, or the perfect plan to arrive first

This stage responds to honesty, not pressure.

Stage 3: Preparation — “I’m getting ready… carefully.”

Stage 3 is where change starts to take up space in your calendar, kitchen, cupboards, and conversations. You’re no longer just thinking about it. You’re arranging for it to come to fruition.

You buy the shoes. You order the thing. You clear a drawer. You tell yourself, “Next week I’m going to do this for real.” You don’t want the pep talk. You are ready for the plan that won’t collapse the moment life bumps into it.

On the inside, Preparation often carries a particular kind of tenderness. Hope, yes. Determination, yes. And also a quiet vigilance—like part of you is watching closely, waiting to see if you’ll follow through or get hurt again. The inner dialogue can sound like: I’m trying. I’m getting set. I’m building toward it. Just don’t ask me to jump too fast.

Preparation is a capacity-building stage. You’re gathering resources—sleep, nourishment, support, rhythm—so the “doing” doesn’t become a flare, a crash, or a shame spiral. It’s the stage where your nervous system is testing the water: Is this safe enough to begin? Will I have enough to sustain it?

Society doesn’t love Preparation. It’s not sensational. It’s not a before-and-after photo. It doesn’t look like discipline from the outside. It seems like “still not doing it,” even when something important is happening under the hood: scaffolding.

So people may push you toward Action too early. A friend says, “Just start already.” A provider hands you a full protocol, with everything laid out step by step. An app gives you a 30-day challenge and calls it “simple.” You hear: perform! And your system may answer: freeze… or sprint… or disappear.

Preparation actually needs a design that respects friction.

You don’t need a perfect plan. You need a plan that can survive Wednesday—the late meeting, the sick kid, the inadequate sleep, the unexpected bill.

You don’t need more intensity. You need one commitment with a handle—precise, small, repeatable.

You don’t need to prove you’re serious. You need support that lowers the cost of starting.

Here are a few lived examples of Preparation done well:

A caregiver wants to shift her eating patterns, so she stops trying to overhaul dinner and starts by making mornings steadier—protein she can grab without thinking. It’s not glamorous, but it is stabilizing. It makes everything downstream easier.

A 59-year-old woman wants to begin strength training. Instead of jumping into a punishing routine, she books a session with a trainer, chooses three movements, and builds recovery into the plan. The win isn’t more or heavier. The win is sustainability.

If you’re in this stage, you can ask a different set of questions—questions that speak the language of readiness:

What’s the smallest version of this that still counts?

What’s the likely snag, and how do I soften it?

What support makes this feel like contact and progress instead of an edge?

You’re probably in the Preparation Stage when:

you’re taking small steps that look “too small” to other people, but feel doable to you

you’ve arranged support (time, reminders, accountability, groceries, rides, childcare) to help sustain your effort

you feel a mix of readiness and nerves—like you want to begin, and you want to begin safely

you’re choosing options that reduce resistance instead of chasing the “ideal” plan

Preparation is not hesitation.

It’s construction. It’s your system building the on-ramp instead of leaping off the ledge. You are getting ready to hold what you’re asking of yourself.

Stage 4: Action — “I’m doing it. And it’s not glamorous.”

This is the stage that photographs well. It’s the stage that gets the most praise. The stage people point to when they say “change.”

You’re buying the groceries and eating the breakfast you planned. You’re taking the supplements you said you’d take. You’re leaving earlier for the walk. You’re turning the phone face down at night. You’re making the appointment, having the complicated conversation, and keeping the boundary you used to break.

From the outside, Action can look like momentum.

From the inside, Action may feel like exposure.

There’s a rawness to it. You’re occupying a new life in your same old world. You’re changing a pattern while still living with the people who know you by the old one. You’re trying to stabilize your body while it's still doing what it’s done for years. You’re asking your body to tolerate novelty—new food, new timing, new routines, new “no’s.”

And novelty comes with a cost.

Action requires energy every day, not just a single shot of inspiration. It asks for choice in moments when you’re tired, hungry, stressed, or overstimulated. It asks for follow-through when the reward hasn’t arrived yet, and may not for some time. (That’s rough.)

Your biology has a vote here. In Action, demand rises. You’re spending more resources: more executive function, more planning, more emotional regulation, more logistics. When the foundation is shaky—sleep thin, blood sugar unstable, pain loud, stress high—Action can feel like pushing a heavy cart uphill. The effort is real. The fatigue is real. The temptation to declare it “not working” is also real.

““You don’t have to be great to start, but you have to start to be great.” ”

I’ve found that this is where people get confused and start blaming themselves. The protocol is “right.” The plan is “right.” Their effort is sincere. Then the symptoms surge, the cravings spike, the mood drops, the fatigue deepens—and they assume they did something wrong.

Sometimes it’s simply the cost of transition. The body notices the change and protests. The inner council gets noisy. One part of you wants change; the other, the familiar. One part says, Keep going. Another says, Stop, this is too much.

Action is where those voices stop being theoretical and start showing up at 9 p.m. every Tuesday.

Popular culture responds to Action with a particular kind of pressure: intensity-as-proof.

It praises streaks. It rewards all-or-nothing. It sells “discipline” as a personality type. It treats pacing like weakness, and it judges rest like you’re falling behind. In wellness culture, it can look like the rigid protocol delivered with a wink: You can do hard things (the self-imposed sort vs. the what-life-has-dealt-us kind). In real bodies, that often translates to: Override your signals.

Even in clinical settings, Action can get unintentionally weaponized. A practitioner senses your readiness and hands you the complete overhaul—food eliminations, fasting windows, workouts, supplements on a schedule that requires a spreadsheet. You start strong, adrenaline carries you, and the plan becomes a performance. Then life hits. The body hits. The wheels come off. And the story you tell yourself is the old one: I can’t follow through. Or Something must be wrong with me.

Action isn’t where you need more moral pressure.

Action is where you need protection.

“Intensity makes for a good story. Consistency makes for good results.”

Pssst…. The plan isn’t the protection

And I want to name something I’ve watched for years, from inside the professional world. I saw it in the classrooms where I taught. I saw it in colleagues’ posts and books. I heard it in podcasts and online summits, in interviews where “help” sounded like a list of directives delivered at speed. There’s a quiet prestige in being the clinician who can rattle off the protocol—the one who knows what to test, what to cut, what to add, what to do next.

But too often, the performance of knowing gets mistaken for care.

I’m sorry to say… it’s not.

A protocol doesn’t live in a vacuum. It lands in a real kitchen, a real budget, a real work schedule, a real body, and a real history. When the plan ignores that, the burden doesn’t fall on the plan or even the supposedly all-knowing practitioner. It falls on you, the patient. You carry the responsibility. You carry the shame when it collapses.

I spent years teaching clinicians that if we’re not careful, “knowing what to do” can become an act of ego instead of an act of compassion. Knowing is not care.

Now I want to speak directly to you, the patient: those full-on protocols aren’t a verdict of your capacity. They have not met you where you are.

So scrap all the advice and let’s learn to meet ourselves where we are.

What’s going to help you the most is pacing you can keep, not intensity you can’t. Structure that includes recovery. A proposal with the right training wheels. A plan that respects the fact that you still have a life to live while you’re changing it.

Action responds well to:

A minimum effective dose. The smallest version of the behavior that still moves the needle.

Rhythm. Meals that stabilize blood sugar: Protein, fat, and fiber at every meal or snack make your day less fragile. Sleep that gets defended like medicine. Movement that regulates more than it “burns.”

Recovery. One hard day followed by a softer one. Space for restoration. Co-regulation—someone safe to text, talk to, sit near, laugh with.

Planning for friction. A “when-then” that keeps you from getting thrown off course: When I miss, then I return. When I flare, then I scale down—not quit.

And something else matters here too: language.

In Action, your words become part of your physiology. If you narrate every stagger as a fiasco, your system tightens. If you narrate the falter as body and life intelligence, your system stays in relationship with you.

“Your falters aren’t failures. They’re body and life intelligence.”

So this stage benefits from a different kind of inner script:

“I’m doing something new. Of course it feels tender.”

“My job is return, not perfection.”

“I’m building capacity. I’m not proving my worth.”

You’re probably in the Action Stage when:

you’re actively doing the new thing, and it takes attention most days

you feel both proud and tired—like you’re carrying something that matters

you keep meeting the moments where the old pattern calls your name

you’re tempted to go harder when what you actually need is steadier

you’ve had at least one moment of “I slipped,” and you’re deciding what that means

This stage responds to pacing, not performance.

Stage 5: Maintenance — “Now I have to keep it.”

Maintenance starts after the initial surge fades.

The new habit isn’t new anymore. The novelty wears off. The praise quiets. The results may plateau. The thing that felt like a clean “before and after” turns into another Monday.

On the inside, this stage can also feel strangely delicate. You’ve proven you can do it—and now you have to keep doing it without the adrenaline of starting or the external admiration. You might miss the intensity. You might wonder if you’re doing enough. You might feel like you can’t keep it up. And you might quietly bargain: Maybe I can loosen this one thing.

You might also feel the weight of it: Is this just my life now?

Your body learns through recurrence. It trusts what it replays. Maintenance is regulation through repetition. Predictability lowers the load. Rhythm becomes medicine. Not “perfect compliance,” but the steady return to what works. And the body notices when the ground is consistent. Your baseline becomes non-negotiable.

The algorithm doesn’t reward this stage. It can’t package it. It can’t sell it. There’s no clean reveal—just repetition, repair, and the daily act of coming back. Maintenance is mostly invisible labor: choosing breakfast again, walking again, going to bed again, saying no again, saying yes again. It can feel oddly lonely to keep showing up when nothing about it looks impressive from the outside.

And even in clinical spaces, maintenance gets misunderstood. A practitioner sees you’re “doing better” and may assume you can handle more—more restriction, more goals, more optimization. Or they take away support too quickly: fewer check-ins, less support, minimal contact. Either way, the message can land as: You should be able to do this on your own now.

But Maintenance isn’t independence.

Maintenance is relationship.

Its important to note that Maintenance can make us a little forgetful. Once something becomes normal, we lose sight of how much scaffolding it once required. Our “non-negotiables” start to sound like common sense—and we can unintentionally demand them from people who are still building capacity.

What helps here is not idealism—it’s structure you can live inside. Backing, not rules. A “minimum viable” version of the plan for the weeks when life gets loud. A clear response for the predictable stressors: travel, holidays, grief, a flare, a hard season at work, or relationship discord. And one simple agreement with yourself: When I slip, I return. I don’t punish.

The real skill of Maintenance isn’t never falling off.

It’s knowing and trusting the on-ramp and building a way back to it.

You’re probably in the Maintenance Stage when:

the new choices feel mostly ordinary

your biggest challenge is consistency, not knowledge

the risk isn’t failure—it’s drift or distraction

a lapse scares you more than it should, or tempts you more than you expected

Maintenance responds to rhythm, not intensity. It’s a relationship with reality, not a finish line.

Now you know the stages.

If you recognized yourself in more than one, good. That’s honest. We move like a constellation—different domains, different readiness, different stakes, and certainly different aspects of life.

And yet the point isn’t the label. It’s noticing where readiness lives—and where it doesn’t. It’s being mindful of what happens when the next step asks more than you can spare.

I can write the blog, create the post, eat my rainbow, take my supplements, get to bed on time, and show up for dance class four times a week. But I negotiate away time at the gym lifting weights, and still have a stack of unopened mail and logistical duties that desperately need my attention.

You’re no different. You may prepare dinner for your neighbor who just got out of the hospital without even thinking about it. Or show up to clean out your best friend’s closet. That doesn’t mean you’re as ready to organize your spice drawer or start the new practice you’ve been contemplating.

Which is why the most crucial part isn’t memorizing the stages.

It’s awareness of when the next step is too big for the life and body you’re carrying it in.

That’s the center of gravity we’ll explore. Because once you can locate yourself—once you can feel what kind of step is actually appropriate—you can see the real issue. It’s not motivation. It’s flow.

And when you’re out of flow, the goal isn’t a bigger push. The goal is a better fit—a next move your life can repeat.

““Our greatest glory is not in never falling, but in rising every time we fall.””

The hidden reason we burn out

Stage mismatch is what it sounds like: trying to do Action-sized behavior with Preparation-level scaffolding; trying to step into the doing before you’ve built the container.

It’s when the plan is “right,” the intention is sincere, and something in you still won’t go.

Mismatch is not sabotage. It’s a signal. It’s the body changing the subject when the ask exceeds capacity. It’s what happens when you attempt an Action-stage behavior while your physiology—or your life context—is still in an earlier readiness phase.

Again, we can watch the mismatch happen in real time...

Your best friend decides to “quit coffee” from an Action impulse while they’re still in recovery mode—sleep shabby, stress running hot. They white-knuckle three days, then “mysteriously” cave on day four. The story becomes an identity and character conclusion: I’m addicted. I have no willpower. The reality is load. Caffeine isn’t just a habit here—it’s a bridge: from exhaustion to functioning, from fog to focus, from “I can’t” to “I have to.” That’s Action energy in a system still building capacity.

Your partner goes for the clean, brave, emotionally fluent conversation with Action intentions, but without the Preparation-level conditions that make that conversation possible—enough time, enough calm, enough margin. The first tone shift hits, and they default to the old pattern: interrupting, defending, collapsing, apologizing for having needs, or going ice-cold. The story may become, “I’m bad at relationships.” The reality is stage: Action effort without Preparation scaffolding.

Your niece starts a new Core Power Yoga class with Action energy from a body that’s inflamed, underfed, dehydrated, and depleted. They push through the first week on adrenaline. Then the flare arrives—pain spikes, fatigue deepens, mood tanks. The story becomes body betrayal. The reality is timing. They asked for strength and stamina from a life still needing to settle. That’s an Action plan landing on an under-resourced body.

It’s easy to recognize stage mismatch when it’s someone else’s story.

Harder when it’s yours.

So here’s the message in the bottle: When we call stage mismatch “lack of discipline,” we render a guilty verdict against the body.

And verdicts don’t stay neat. They invite shame. Shame recruits a narrator. It starts speaking in identities:

I’m lazy.

I’m unreliable.

I never follow through.

This is just who I am.

And shame rarely stays alone. It often recruits blame.

At first, it may be self-blame: I’m impossible. Then it can shift to body-blame: My body won’t cooperate. My body is sabotaging me. And sometimes it spills outward: No one supports me. Nothing ever works.

Blame can feel like clarity. But it’s usually just pain looking for somewhere to land.

Blame is the reflex. Orientation is the skill.

And we build whole selves out of human moments—moments that were never meant to be character assessments. They were meant to be information. Information about capacity. Information about timing. Information about what stage we’re in and where to start.

And I’ll gently complicate my own argument here: stage-based frameworks aren’t magic wands. Even in smoking cessation research—the place the Stages of Change model first gained traction—“stage-matched” approaches aren’t automatically superior to other ways of supporting change.

So no: I’m not offering stages as perfect science or failsafe labels. I’m not using them to explain every stuck place. I’m offering stages as a compassion technology—a way to stop reading “not yet” as moral failure, and start reading it as guidance.

The edge: why most advice backfires

The truth is that most advice is Action-coded.

And you can’t use optimization tools for stabilization—no matter how convincing the plan looks on paper.

The plan assumes time. It assumes money. It assumes support. It assumes a bandwidth. It assumes a body that’s sleeping, eliminating, and stabilizing blood sugar. It assumes a life with ample wiggle room.

Then it gets delivered as a universal truth—and the person who can’t hold it is treated as the problem.

Systems do this too. Healthcare systems. Workplaces. Families. Institutions.

They demand change without conditions. They ask for transformation and performance while keeping people in the exact circumstances that make transformation expensive.

And the optimization marketplace profits from that gap—it sells you the idea that if you just had the right plan, you’d finally become the kind of person who follows through.

So the shame sticks to you, when it belongs to the mismatch.

The shame economy

Shame isn’t a private emotion. It’s a social one.

It rises in the space between who you are and who you believe you’re supposed to be—the you that can be accepted, admired, and approved of. Shame is the feeling of being seen “wrong.” Not wrong in behavior. Wrong in being. It’s the nervous system registering a threat to belonging.

And during transition, shame has more opportunities.

Transitions scramble the rules. The old identity doesn’t quite fit, the new one isn’t stable yet, and the world keeps offering opinions in the form of advice. When life is rearranging you—new diagnosis, new role, new season, new limitations—shame steps in as an enforcer: Get it together. Get back to normal. Don’t be the person who can’t.

Shame is what happens when a transitional nervous system gets treated like a character flaw.

It’s also a remarkably efficient tool of social control.

Shame tells us what the group rewards and what it punishes. It teaches the boundaries without needing a lecture. In some rooms, the boundary is thinly disguised as “motivation” or “discipline” or “perfection.” In others, it’s dressed up as “accountability.” Online, it’s optimized for speed: a quick judgment, a pile-on, a permanent record. The feed doesn’t just distribute information—it distributes belonging.

And when shame gets activated, it doesn’t make change easier.

It makes you smaller.

We withdraw. We hide. We go quiet. Or shame flips into rage—defensiveness, argument, contempt—anything that keeps the soft underbelly from being touched. That’s the anatomy: shame threatens connection, the body protects belonging, and the behavior is the visible tip of that protection.

So when we call mismatch “lack of discipline,” it isn’t only inaccurate. It’s socially contagious. It teaches you to treat your own nervous system like it’s failing a public test—right at the moment you need partnership and pacing; actual care.

Ending as change: the same stages, a different task

And this is where I have to be truthful about my own life again—because it’s easy to talk about readiness as a principle until you’re living inside a transition. I used to think the stages were mainly about doing the right thing—following through, becoming the kind of person who does what they say they’ll do.

But the longer I’ve watched bodies and lives in motion—especially my own—the more I think the stages are really about something else:

They’re about facing reality.

Not just contact with a new habit, but contact with a reality you can’t unknow. A diagnosis. A limit. An ending. A truth that costs you something. The moment you realize you can’t keep living the old way—not because you lack willpower, but because the old way no longer fits who your life is asking you to be.

And sometimes the hardest change isn’t starting. It’s ending.

I spent a long time trying to rescue something I loved from a structure that no longer matched its values. I kept treating that as an achievement problem—if I were determined enough, strategic enough, positive enough, I could outwork the mismatch. I was living on output and adrenaline. And I was asking for Action inside constant friction—misaligned priorities, mismatched definitions of care, competing objectives. I wasn’t stalled, far from it. I was working my tail off. I was producing, pushing, fixing, trying to make it work—yet the progress I was chasing never arrived.

And that’s when I realized: I wasn’t in a behavior-change problem. More action wasn’t the answer. It was an ending problem. I was trying to use Action to outrun acceptance. The model doesn’t only map how we start new behaviors. It also maps how we come to terms with an ending—and make the cut when we’re ready.

Same stages. Different task. Not “how do I start?” but “how do I end what I can’t keep carrying?” From this angle, the stages looked more like this:

Precontemplation: I can’t look at the ending yet.

Contemplation: I can feel it’s over… and I can’t let it be over.

Preparation: I can start building the off ramp—support, structure, language, container.

Action: I finally make the clean cut: the email, the meeting, the decision, the boundary.

Maintenance: I live inside the after: temptation to re-open, bargaining, grief spikes, returning to the chosen line.

This is why “just do it” collapses so often in transition. Because, as I’ve noted, transition isn’t primarily behavioral—it’s relational and symbolic. It’s identity. It’s belonging. It’s uncomfortable. It’s heartbreak. It’s readiness deciding whether the truth can be held.

In the beginning, we rarely face an ending head-on—unless the ending arrives unasked for; unless life forces it onto the table. Instead, we move around it. We keep the envelope on the counter. We keep the conversation unsaid. We tell ourselves we’ll deal with it when we have more bandwidth—or when it stops feeling so dangerous to face.

From the outside, it can look like procrastination or avoidance or maybe even nothing at all—continuing on with the everyday routines that keep you moving. From the inside, it’s often something more specific: a reluctance to face what the ending might mean.

Then the truth starts showing up at the edges. You can feel it’s over… and you keep looking for the clause that makes it not over. You gather information, run scenarios, try one more game plan, give it one more week. Hope stays close enough to warm you. Distance stays close enough to protect you.

And eventually—sometimes through support, sometimes through exhaustion—you start building a ramp. It’s just enough structure to make contact survivable: the right language, the right people, the right container, the right frame.

Action, then, is rarely a burst of motivation. It’s a threshold. One send. One line in the sand. One encounter where you stop arguing and speak authentically.

For me, it came in a flash—though I’d been walking toward it for years. There were three options: A, B, and C. Option A meant more of the same effort in a direction that had stopped yielding any results. B meant contorting myself into something I couldn’t respect. And C meant choosing the ending I’d been skirting—necessary, clean in principle, and complicated in practice.

And Maintenance is the after. The part where the body reaches back for the familiar. The part where bargaining returns—maybe I can soften it, maybe I can make it work, maybe I overreacted. The part where I keep choosing the line I drew, not with intensity, but with faith and allegiance.

And that’s the point I want to make plain: the stages aren’t only for starting. They’re for any moment that asks you to make contact with change—beginning, ending, or living in the in-between. Stage recognition doesn’t judge you. It orients you. It tells you which step is actually possible from here.

Readiness as dignity

In the last Passage, we talked about the Window of Tolerance—what it looks like when your nervous system has room to adapt to change, and what it looks like when it doesn’t. That matters because so many of us have been trained to interpret overwhelm as a personal failure.

This Passage is the next step because once you can recognize your state, the question becomes practical: what stage am I in—and what kind of step is appropriate from here?

Remember this: The Stages of Change aren’t a moral ladder. They’re a location pin. They tell you where you are before you start taking directions from people who have never lived inside your body, your budget, your schedule, your diagnosis, your responsibilities, or your grief.

And that matters, because most modern advice is essentially one long sales pitch for Action—issued like a directive by people who won’t have to live the fallout.

That advice often assumes you have slack. It assumes you have support. It assumes you’re resourced enough to mistake control for care—and to call that “discipline.” Then it hands you an overhaul and calls it empowerment—as if “should” didn’t cost anything.

So the work here isn’t “try harder.”

It’s recognition.

The kind that slows you down long enough to tell the truth: If I force this, I will pay for it. If I stay here forever, I will also pay for it. So what is the next honest step my life can repeat?

That’s where dignity lives—not in big performances of discipline, but in refusing to let a culture of optimization turn your nervous system into a test you’re constantly failing.

And life will keep testing that dignity.

There will be days when you’re ready and days when you’re not. Days when you can return easily, and days when returning may require a kind of self-override that looks like “willpower” from the outside and feels like self-betrayal from the inside.

Some days the answer is: return.

Some days the answer is: redesign.

And some days—especially in transition—the answer is to name the real task: this isn’t a pattern. It’s a threshold.

So if you take one thing from this Passage, let it be this:

Don’t measure yourself by whether you can perform Action. Measure yourself by whether you can recognize the stage you’re in—and then, only then, choose the step that keeps you intact.

For me, that sometimes means I still don’t sign the page—I just sit with it long enough to stay with its meaning.

And that’s not lowering the bar. It’s not procrastination.

That’s dignity.

Dignity is refusing to outsource your self-trust to a culture that profits from your self-override. And it’s how change becomes possible—whether you’re beginning something new, or finally ending what you can no longer hold.

There are 8 Passages in this series. You’ll find the next Passage 7: The Rhythm of Transition here.

References:

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.390

Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The Transtheoretical Model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38

Riemsma, R. P., Pattenden, J., Bridle, C., Sowden, A. J., Mather, L., Watt, I. S., & Walker, A. (2003). Systematic review of the effectiveness of stage based interventions to promote smoking cessation. BMJ, 326(7400), 1175. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1175

Scheff, T. J. (2000). Shame and the social bond: A sociological theory. Sociological Theory, 18(1), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2751.00065

Schaumberg, R. L., & Skowronek, A. (2022). Shame broadcasts social norms. Psychological Science, 33(8), 1257–1277. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976221075303

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345–372. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.