Passage 3: Transitions as Care (who holds you in the in-between?)

The first time Isamu was admitted to the UCSF Medical Center, I left the hospital at 3:00 in the morning, carrying his absence in a plastic tote bag.

His jeans. The T-shirt and flannel he'd arrived in. His socks and shoes, still holding the shape of his feet. The nurse had helped me peel his clothes off earlier that night, when his headache became unbearable and he could no longer sit upright without vomiting. They were ordinary things, but once they were in my hands instead of on his body, they became evidence: he's not just here for a quick test or some medication to ease the pain. He's staying. This is bigger than a sinus infection. I've just left my husband in the hands of modern medicine.

Earlier that evening in the Emergency Room, while we waited for the scan, there hadn't been a bed for him. We were parked in the hallway on a gurney, me sitting by Isamu’s feet, my own legs dangling off the high cot like a child’s.

Light

Dark

It wasn’t until midnight that they ran a CT scan. They found lesions on his brain, but no one could say what they were yet.

Finally, in the early morning, they admitted him to South 8—the Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Neuro Transitional Care unit. Once he was settled, I kissed his forehead. The nurse told me it was time to go, and I didn’t argue. I just moved—like my body already understood what my mind hadn’t caught up to: we weren’t in charge anymore. I left him in that dim room with a pain drip and a stranger lying behind the curtain, and stepped into the bright, quiet hallway. Alone.

“I just moved—like my body already understood what my mind hadn’t caught up to: we weren’t in charge anymore.”

The air in the corridor felt thinner than in his room. It was harder to catch my breath, as if I were suddenly standing at a new altitude. Breathe, Andrea. Somehow, my body carried me down the hall, past the nurse's station where I caught Isamu's name handwritten on a dry-erase board, around the corner past the Neuro ICU, into the elevator, and back out the sliding glass doors where we had entered together eight hours earlier. It was a route I would come to know well, though I didn’t know that yet.

By the time I crossed the empty street to the parking garage, paid the attendant, and crested the hill overlooking the valley in our silver Honda Accord, the world outside had come back online—streetlights humming, traffic signals cycling, the city completely uninterested in the fact that Isamu was lying in a hospital bed with a mass growing in his brain.

Clinically, it sounded straightforward. Intolerable headache. Abnormal findings on a late-night brain scan. Admission for further assessment. Pain managed. Status stable.

The chart didn’t mention that I was also seven weeks pregnant.

And in reality, nothing about the path ahead was straightforward. A transition had begun—an unmarked ending of a life in which a headache simply meant ibuprofen and rest. Not CT scans. Or spinal taps. Not wards with names like "South 8" in the neurology department.

I was no longer a wife who could assume tomorrow would look like yesterday or any other Sunday. Isamu was no longer the healthy 31-year-old who spent mornings reading the paper, drinking coffee, and listening to CDs before a week of coding.

Without anyone naming it, we had already stepped off the common path and into an in-between.

In Passage 1 of this series, we named that early phase as an ending—the moment when the body recognizes "no more" before the mind can even say what's gone. In Passage 2, we saw how many cultures surround those endings with ritual, so the in-between is treated as a rite of passage rather than a personal defect or a non-event. When that kind of holding is absent, what hurts is not only the sense that you're "not handling it well," but the loss of something vital: the right to the rite itself—a passageway between two divided realities. The transition is real, but it goes unspoken and unmarked. You cross a threshold with no witness.

What I didn't have the words for, back on that first night at UCSF in April 2000, was that this was also a transition of care.

Isamu was moving from autonomy to dependency—handed over to the protocols and pacing of a hospital, his care administered by strangers. And I was moving from spouse to care coordinator: still his person, but now also his advocate, his translator, the one who would carry the through-line when everything got scattered.

We were crossing thresholds on multiple levels at once: from home to hospital, from independence to patient, from partner to caregiver. We slipped from ordinary time into the strange, elastic time of tests, scans, rounds, and results, and from deciding where to go to being told. The setting changed. The roles changed. And the care—who gave it, who received it, how it moved between us and the institution—changed, even though no one wrote that down in the chart.

“What looks like a single health event is actually a life reconfiguring.”

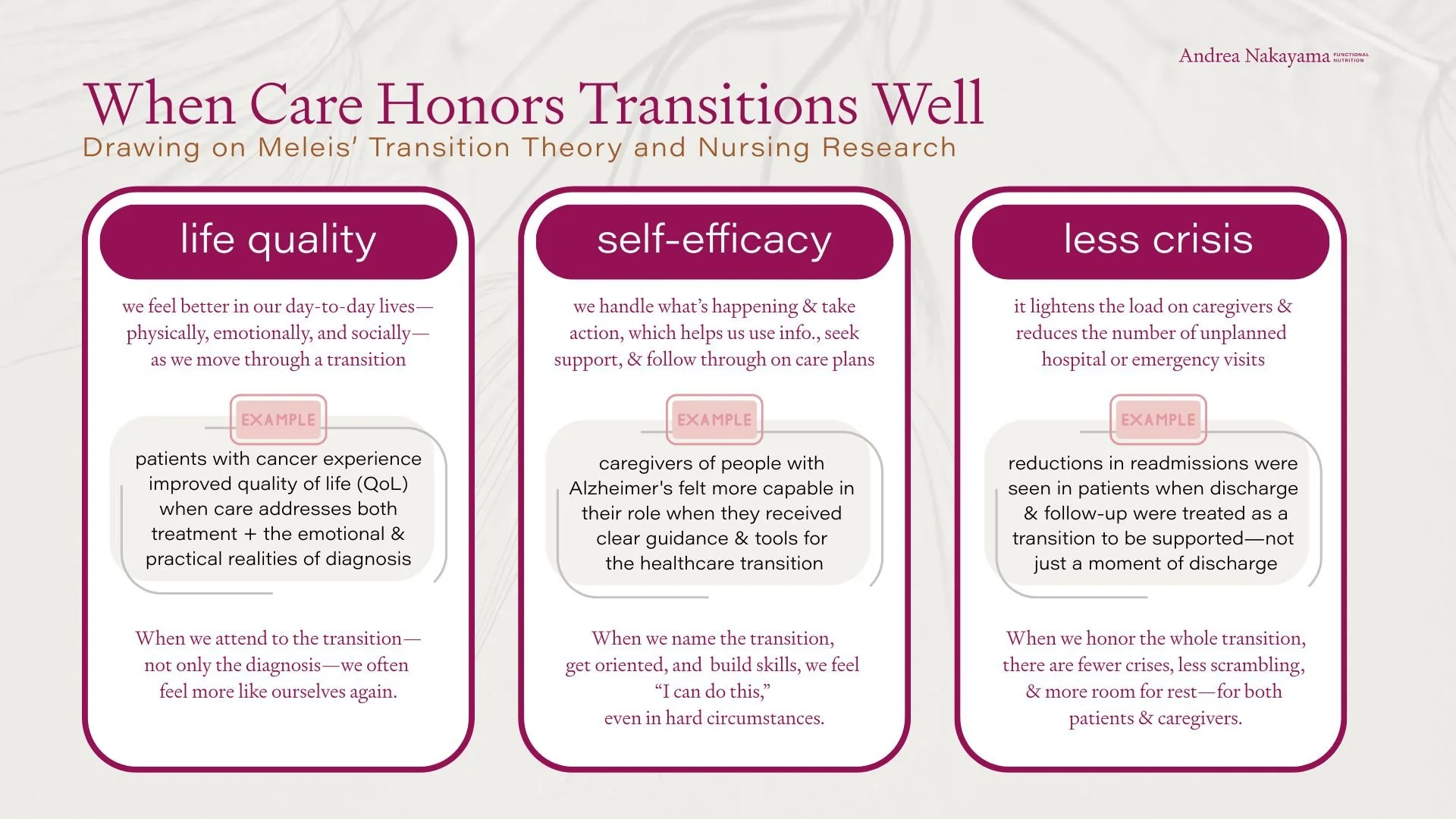

Now, as I read the work of nursing scholar Afaf Meleis, I recognize that night in her model. Meleis identifies these crossroads as "transitions,” underscoring that they aren’t just finite events, but processes that unfold over time. Her Transitions Theory was developed to help nurses see and support what I was experiencing on that hill near the UCSF parking garage: that what looks like a single health event is actually a life reconfiguring.

This third installment explores that layer of the story: how a transition in health becomes a transition of care. When the body changes and the power to steer time, information, choices—quietly transfers to others. Who takes over? Who translates? Who tracks the story when it splinters into shifts and specialties? And what happens in a body—energy, appetite, fear, resilience—when that crossing is well-held… or when it isn’t.

For Isamu, the transition was clinical: pain drip, tests, strangers entering in the night. For me, it was logistical and existential: learning new terminology, tracking details I couldn’t afford to forget, making decisions while pretending I wasn’t terrified. No one prepared us for any of that. The medical crisis was addressed; the transition—that human recalibrating that also needed care—was not.

“A transition isn’t just a threshold. It’s a human recalibration—and it’s too often left unattended.”

Meleis' Transitions Theory in Nursing

By the time we reached South 8, Isamu and I entered that corridor with more than just symptoms. We were still clinging to the assumption that we were the authors of our existence—and stunned as we learned we weren’t. We stepped into that unit with a naïve faith in expertise and no initiation to its vocabulary, pace, norms, or rules.

Our personalities came with us, too: Isamu’s stoic and deliberate instinct to minimize and keep going, my impulse to track, translate, and hold the through-line. And beneath it all were private stakes no one charted: my pregnancy, our youth, our disbelief that life as we knew it could change shape so fast.

Some parts of that night were efficient. But the experience of the transition—the human recalibration happening inside both of us—was largely unattended. That gap is where Meleis’ theory gains significance.

For nurse-researcher and nursing scholar Afaf Meleis, that night wouldn't just be "a hospital admission for a neurological issue." Over the last four decades, she's developed a way of marking moments like these as their own sort of corridor—threshold experiences where life reshapes itself, often before anyone has language for what’s happening.

In her work, a transition isn't just change. It's the lived process of that shift from one configuration of meaning, identity, and daily patterns to another. It has the now-familiar beginning (often before anyone names it), middle (full of questions, disruptions, and adjustments), and an endpoint that's usually clearest in hindsight.

What defines a transition for Meleis is not only what happens to someone, but what it does to their sense of self, their relationships, and their competence over time—especially where care is involved.

Meleis describes several types of transitions:

Developmental – postpartum; menopause; aging into new physical limits

Situational – becoming a caregiver; a sudden injury or accident; taking the keys from a parent; moving someone into assisted living, or having to move there yourself

Health–illness related – diagnosis; treatment; hospitalization; rehab; hospice or palliative care

Organizational – infrastructure changes that reshape continuity: new portals/systems; staffing shifts; discharge processes that drop handoffs

Not all transitions feel the same. Some are chosen, some imposed. Some are anticipated, others arrive like a rupture. In short, Meleis shows us that in healthcare, a transition isn’t just what happens. It’s defined by what it requires of a person—and whether the care around them raises to meet it.

““Transition is both a process and an outcome. It involves movement from one state to another and the achievement of a new level of stability, health, or well-being.””

Why transitions are clinical: vulnerability in the in-between

Meleis insists that transitions are inherently susceptible times, opening up both risk and possibility: symptoms can worsen or improve, identities can fracture or reorient. People can feel perplexed, unseen, or abandoned. Or, if supported, they can feel accompanied, informed, and better able to adapt.

Whether a transition becomes an injury or an initiation depends, in large part, on the conditions surrounding it. The same diagnosis can land completely differently depending on who is with you, what you’ve lived through, and how coherent—or strained—the system is.

Personal, family, community, and organizational conditions shape how the transition is lived. They also shape how it feels inside you: grief, abandonment, fear, shame, a quiet sense of betrayal. And all of that informs how the body responds—through sleep, inflammation, pain, blood pressure, mood, and so on.

“Whether a transition becomes an injury or an initiation depends, in large part, on the conditions surrounding it. ”

That first night at the hospital with Isamu, some parts were relatively smooth: the scan once scheduled, the pain addressed, a bed finally available. But the rest was bumpy in the ways that matter most during a transition: we weren’t oriented, we didn’t know what to ask, and the processes moved faster than our bodies could process. It wasn’t only that Isamu was sick. It was that we were suddenly navigating new terminology, new rules, and new power dynamics—with almost no scaffolding. That’s the difference Meleis is pointing to: treatment can be competent while the transition is still unheld.

Transitions live in charts and in cells—in lab values, but also in the lived experience we can track to understand the impact on our everyday behaviors and patterns.

Who’s the theory for?

Meleis developed her Transitions Theory as a framework for nurses—the people who often stand at thresholds: admission and discharge, pre-op and post-op, diagnosis and “go home and wait,” birth and postpartum, treatment and survivorship, even death. Nurses are witnesses to what a chart can’t fully hold: the moment a person crosses from one version of life into another.

While this lens can apply to many kinds of change—developmental, situational, organizational—in this passage, I’m staying close to health transitions that become transitions of care: the moments when the body changes, the roles around it change, and the authority over time, information, and decision-making is transferred—quietly, quickly—to strangers, systems, or whoever is on shift—clinically or at home.

“For patients and caregivers, sometimes language is the first kind of care. ”

For patients and caregivers, Meleis offers language—and sometimes language is the first kind of care. Oh. This is why I feel disoriented. I’m not “failing at coping.” I’m in a transition. Something in me (and my life) is rearranging.

For clinicians and practitioners of all kinds—nurses, physicians, nutrition professionals, therapists, health coaches—this framework is a reminder that the moment someone “becomes” a patient is not merely clinical or administrative. It’s an identity shift. A competence shift. A relationship shift. A safety and agency shift.

If we treat it as a logistics problem only, we miss what’s actually happening inside the person.

And for systems thinkers like me, this model highlights the fault lines: where people are most likely to fall through the cracks because the clinical landscape doesn’t recognize that it’s asking them to cross a threshold with no handrail.

“If we treat transitions as a logistics problem only, we miss what’s actually happening inside the person.”

I’ve trained thousands of healthcare providers over the last fifteen years, and I’ve seen how easily the human experience of that crossing gets diminished or bypassed. The realities of what’s lived in the body—beyond the signs, symptoms, or diagnoses—are often eclipsed by the search for the fix, the impulse to save the day, to solve. Of course, in a true emergency, medical intervention must take precedence. You stabilize first. But in chronic care—and in the long aftermath of an acute event—Meleis reminds us that myriad aspects must be held at once: the treatment plan and the transition.

Even after the crisis has passed, we have to reevaluate what changed—what was lost, what began, and what the body has been carrying ever since.

If you’re an “advanced patient,” an advocate, or a practitioner who is also a person in a body, this is a way to see your own passages more clearly, too.

How transitions unfold

In Meleis’ framework, transitions have three key elements:

Properties: clues that a transition is underway

Conditions: the personal, family/community, and system factors that ease or complicate the crossroad

Patterns of response: the signals—in bodies and lives—that show whether a transition is being integrated or overwhelming someone

I’ll admit: on first read, Meleis can feel like a lot—categories, terms, sub-terms, a model that can look more like a syllabus than a lifeline. But I don’t use her work as a checklist. I use it to ask better questions in the moments when a body—and a life—are reorganizing. You don’t need to memorize this. You only need to let it widen what you consider “clinical” or even a part of the healing paradigm.

If I translate her rigor into lived terms, it becomes surprisingly simple: Do you know what’s happening? Do you have any say in it? And is anyone helping you make sense of the change you’re living through? That’s what the model is trying to protect.

Meleis names the part that rarely makes it into the clinical notes: the body that can’t settle, the mind that can’t hold information, the life that suddenly runs on appointments and uncertainty. That’s not “poor coping.” That’s a nervous system trying to re-map the world mid-crisis.

So if the theory starts to float away from you, grab it by one anchor: What would it look like to care for the transition—not just treat the condition?

Properties: how you know you’re in a transition

Some of the properties Meleis names include:

Awareness – Do I recognize that something is changing?

Engagement – Am I able to participate in decisions and preparations?

Change and difference – What is actually different now in my roles, routines, and body?

Time span – Is this sudden, gradual, prolonged, or cyclical?

Critical points or events – Are there moments (a test result, a discharge, a biopsy, a scan) that intensify the transition?

I name these so that we can recognize them in the wild, where care is often thinnest. These properties provide data on acclimation, agency, and the abruptness of life’s reconstruction.

Conditions: what makes the trek easier—or harder

The conditions are the context in which all of this unfolds: what you bring with you, what’s happening in your family or community, and how the wider system is functioning. They don’t cause the transition, but they strongly influence how rough or workable it feels—how much sense it makes, how alone you are in it, and what resources or barriers are present.

Meleis names three broad categories:

Personal conditions – your history with illness or systems, coping skills, finances, native tongue, culture, beliefs, nervous system load, prior losses.

Family and community conditions – who’s in the room (or not), the quality of support, roles and expectations, stigma, practical help, or logistical chaos.

System and organizational conditions – policies, staffing, time pressures, continuity of care (or fragmentation), and how much space clinicians have to actually prepare and accompany, not just document and move on.

Meleis’ invitation to clinicians (and, I would argue, to all of us) is to recognize these upheavals as sites of heightened vulnerability and heightened possibility—and to ask, very concretely:

Who is holding us through this?

What support is present before, during, and after this transition?

And what might a “healthy transition” look and feel like, from the inside out?

Response: how the body tells the truth

Meleis doesn’t treat these crossings as abstract. She tracks what they do in real bodies—nighttime settling, digestion that shifts, follow-through that falters, a nervous system that can’t find its usual baseline.

I’m going to come back to those patterns near the end of this Passage, because they’re often the only “vital signs” that reveal whether a transition is accompanied—or merely processed.

Questions that move us from judgment to care

I don’t have to say “properties” or “patterns” out loud to lean on this model. When I feel myself slipping into judgment—of myself, or of someone I love—I try to pause and ask better questions, especially in seasons when we have less control over our day-to-day than we used to.

Where have I (or they) lost control—and what’s one small choice we can return to?

What information would make this less disconcerting? What needs translating into plain lingo, or repeating slowly, or writing down?

What used to be easy to remember or manage that now needs new practices? A list, a calendar, reminders, a second person in the room, a follow-up call scheduled before we leave.

What is the body asking for right now that would make adaptation more possible? Sleep cues, steadier blood sugar, hydration, nervous system regulation, more straightforward steps, fewer simultaneous changes.

Who is on the transition team—practically and emotionally? And if the honest answer is “no one,” what support can I ask for first, or put in place first?

That’s the point of Meleis theory, at least as I’ve come to use it—not to make anyone fluent in the details, but to make it harder for a human being to be treated as “stable” on paper while unraveling on the inside.

A new diagnosis: bones, buffering, and asking for the care I actually need

I didn’t really understand how portable this lens was until it showed up in my own body again. Not too long ago, I had a DEXA scan that showed osteoporosis in my hips.

In the clinical notes, it was a fairly ordinary health event: a post-menopausal woman, a bone-density test, a set of numbers that slid over an invisible line from "osteopenia" to "osteoporosis."

Here are your scores.

Here's the guideline.

Here's the recommended next step.

It could have been any woman in my age bracket.

In my body, it was anything but ordinary. It was an awareness moment.

In Meleis’ translation, awareness is the first signal that you’ve crossed into a new chapter—often before you’ve decided what to do about it.

Somewhere between the words "your hips" and "osteoporosis," I felt that familiar inner click: oh… something has changed. I wasn't alarmed or distraught (I knew I could work with this), but this also wasn't just about "getting older" or "needing more strength training." It was a different chapter in the story my bones were telling, with real implications for how I move, age, and inhabit my life now and in the future.

“Awareness is the first signal that you’ve crossed into a new chapter—often before you’ve decided what to do about it.”

Because estrogen and bone density are so closely linked, the recommended next step was, of course, hormone replacement therapy. It's also the suggestion on so many lips right now—HRT as the go-to “fix” for midlife women's bodies. It’s easy, in moments like this, to feel moved along an assembly line—data in, recommendation out—while your nervous system scrambles to catch up.

But before you reach for your HRT script or soap box: estrogen replacement therapy isn't a fit for my body. (Yes, despite the "HRT will solve everything" chorus, the incongruity is a reality for some of us, too). So I started looking for other ways to respond to what the scan revealed.

My first act of care was a question: what else is true here, and what options actually fit my physiology?

That's how I found myself in an acupuncturist's office, lying face-down on a table with tiny needles along my hips and torso, intending to support my osteoblasts and circulation from another angle.

But as I sank into the treatment, heat lamps warming the room, another awareness surfaced alongside the images on that scan: how much my physical structure had been holding... for years.

As I spoke with the acupuncturist, I heard myself describe—almost casually—the posture I've long assumed: standing between an audience and backstage chaos and pressure, poised toward the people listening while keeping one ear tuned to the business's chronic needs. Making things seamless and on target "out front" by absorbing impact "in back." I looked on mission from the outside, but my nervous system told another story.

In other words, I'd been using my body as a buffer and a bridge.

I could suddenly see not just a bone-density result, but a convergence of transitions.

From Meleis' perspective, this was:

A developmental transition – this phase of my post-menopausal body.

A health–illness transition – a new diagnosis, and a new level of structural vulnerability.

A situational transition – a required shift in a role after years of serving as that literal and figurative intermediary.

The DEXA scan was a critical point—a punctuating event.

And a critical point isn’t only a result; it’s a hinge. Hinges deserve extra support.

The acupuncture table became a small threshold space, a literal limen. And the larger transition—the one about my work, my identity, my right to step back from being the permanent shock absorber—unfolds over a longer time span that I'm still navigating, in fits and starts.

In an ideal world, moments like this come with more familiarization and follow-up—support built into the moment. In the real world, you often have to construct that scaffolding yourself.

It wasn't just a moment to consider, "What can I do for my bones?"

It was also, "What has my body been asked to hold, cushion, and shield—and how do I acknowledge and lift that burden?"

““Awareness and engagement are essential properties of transitions. Without awareness, individuals may not recognize the need for adaptation; without engagement, they may not take active steps toward change.””

That meant saying to myself and my providers:

"I want to pursue every evidence-informed option for bone density that works with my physiology, not against it."

"I'm in a larger transition in my work and identity—let's take that into account as we pace these interventions?"

"My system is now in an in-between. I need treatments that fortify, not just fix."

And it meant actually naming, aloud, the obvious truth I'd been trying to withstand:

"I can't keep being the buffer in the same way. My bones are telling a truth that cannot be ignored."

At first pass, this might sound like I'm talking only about "energy" or metaphor.

I'm not.

From a Functional Nutrition and systems-biology lens, a long-term encumbrance—chronic stress, responsibility, emotional labor, the posture of constant bracing—intersects with hormone shifts, nutrient status, gut health, and movement patterns that all influence my bone story.

And from a transitions lens, this wasn't just a clinical problem to solve. It was a passage begging to be acknowledged: an ending to the season of "I'll hold it all," and the beginning of something less clear but more honest.

No one handed me a playbook or ritual for any of this.

In more traditional rites of passage, no one crosses alone. There are witnesses. Translators. People whose job is to say: this is big, and you’re not crazy. The absence of that kind of holding is a strain in itself.

There was no formal rite of passage for "the teacher whose hips now need protecting" or "the founder whose bones are tired of defending."

But Meleis’ framework helps me recognize that I was, in fact, in a transition of care and of identity—and that I was allowed to ask for protection that matched that reality. Not because anyone around me missed something on purpose, but because so much of this kind of reorganization happens quietly, without a script or a shared language. A handful of friends and confidants helped hold what the moment itself didn’t. And I’m learning to meet it, too, with a different level of self-care.

And by transition of care, I don’t just mean what was recommended. I mean the pace at which it was delivered, the assumptions underneath it, and the degree to which I was helped to align, participate, and choose.

That recognition has changed how I move through my days:

I'm more deliberate about strengthening and supporting my skeleton—through nutrients, movement, sunlight, and targeted balance and support.

I'm more honest about when I'm at capacity, and less willing to pretend my structure is infinite. (Newsflash: It's not.)

I'm more committed to surrounding these changes with the kind of steady attention I would insist on for any patient: explanation, accompaniment, respect, and room to adapt.

The osteoporosis diagnosis didn't just add a new line to my medical chart. It revealed a passage I was already walking—and invited me to build a different kind of care around it, care that honors both the biology of my bones and the story of how I've used them.

Patterns of response: how your body tells the truth

One of the strangest parts of a medical transition is that the system can move on—orders placed, results posted, next appointment scheduled—while the person is still in the aftershock. These are the signs I watch for, in myself and in others, that the transition is outpacing our ability to keep up.

Physical: sleep that won't cooperate; digestion that suddenly feels finicky; headaches or flares that seem to have "no reason"; blood sugar swinging more easily; a nervous system that startles or shuts down faster than it used to.

Behavioral: missed appointments; procrastinating on lab work, paperwork, or bills; feeling inexplicably avoidant about phone calls or patient portals.

Relational: withdrawing from friends; snapping more quickly; feeling oddly disconnected from a life that still looks the same on the outside.

Meaning-making: you think, Who even am I right now? Or, I can't go back, but I don't know what's next.

In a conventional frame, these patterns get labeled as non-compliance, anxiety, “just stress”—even character.

In a transition frame, they’re data.

“One of the strangest parts of a medical transition is that the system can move on—orders placed, results posted, next appointment scheduled—while the person is still in the aftershock. ”

Especially in medicalized moments—handoffs, portals, speed—this is often where the truth leaks out first: this is a lot; I am reorganizing around something real. And when the passage is better held, you can feel that too—more orientation, steadier routines, small returns of agency.

You don’t have to like what shows up. But seeing it as a passage response—not a personal failure—can reduce the extra pain we add on top of the hard thing and open the door to better support.

A Meleis-inspired pocket practice

Meleis' Transition Theory reminds us that healthy transitions don't depend solely on what's happening to you, but also on your awareness, engagement, and the conditions around you. You can turn that into a small, three-step practice to carry into any threshold moment—an appointment, a discharge, a new diagnosis, even a complicated family conversation.

Think of it as a tiny self-advocacy tool inside a transition of care:

1) Name the transition you're in (awareness)

Before (or even during) an encounter, take a moment to name what's changing deliberately:

"I'm moving from identifying as 'always healthy' to being someone with an ________ diagnosis."

"I'm becoming a caregiver."

"I'm stepping out of a role that used to define me."

"I'm moving from managing my own care to navigating a system."

Remember, naming it to yourself is a way of saying, "This is not nothing." It can help your nervous system understand why everything feels harder than the chart might suggest.

2) Name one thing you need from this moment (engagement)

Health and medical transitions can make us feel like we're being swept along on a conveyor belt. One way to step back into the story of your own care is to choose a single focus:

"The most important thing for me today is understanding what you see as the immediate next steps."

"What I most want to understand is how this change is likely to show up in my day-to-day—energy, sleep, symptoms—over the next month."

"What I most need right now is guidance on what support—people, resources, or follow-up—you'd recommend for someone in my situation."

"Before I leave today, I need to understand who my point person is and what happens next."

If you'd like, you can even say this out loud at the start of a visit: "I'm in a big transition, and my brain doesn't hold everything. The one thing I need to understand before I leave today is ______."

This is self-advocacy in Meleis' terms: participating in your own transition rather than being transitioned around.

3) Name who is walking this with you (supporting conditions)

Finally, ask yourself: Who is part of my transition team? Not just on paper, but in reality.

Is there one friend who "gets it" and can come to appointments or debrief afterward?

A practitioner who can see the whole picture, not just one body part?

A support person, therapist, or group where you don't have to minimize what's changing?

If the honest answer right now is "no one," that's important information too. It might shape the kind of care you ask for:

"I don't have much support outside of this clinic. Can we slow down and make sure I really understand what's happening?"

"This transition feels big, and I'm mostly walking it alone. Are there resources or people you'd recommend so I'm not doing this entirely by myself?"

None of this has to be dramatic.

It can be quiet, almost private.

But each small act—naming the transition, naming what you need, naming who's with you—is a way of treating your passage as real and worthy of care.

In Meleis' terms, to move through a transition well is never only about what's happening to you. It's also about how you're supported in meeting it and how you're allowed to participate in shaping it. That's really what self-advocacy means here—not a solo act of heroism, but a quiet, ongoing practice of naming the passage you're in, asking for the information and pacing you need, and letting your body's responses count as data, not defects. It's the willingness to say, "This is a transition," and then to build even a small circle of care—professional, personal, and internal—around that truth.

As I write this, I keep thinking back to that first night on South 8—how I walked out carrying a plastic bag of clothes and an entire unspoken reassignment of roles. How I drove home through a city at daybreak that was already moving again, and laid down in a bed that still held the shape of “before.” And how I returned to the neuro ward the next day with my fear disguised as competence—already learning the unwritten rules: when to ask, how to ask, which questions “counted,” and what tone made information more likely to be offered than withheld.

If I could give that version of myself over 25 years ago one bit of advice, it would be this: ask for a point person. Ask for the next step in plain language. Ask for the scaffold.

Not because you’re demanding or needy or not smart enough to hold it all—but because you’re crossing something real, and you don’t have to hold it all.

““Transition is both a process and an outcome. It involves movement from one state to another and the achievement of a new level of stability, health, or well-being.””

Next week, we'll turn to the question that lies at the heart of all of this: how a body finds any stability while things are changing. In the vocabulary of physiology, that's allostasis—"stability through change." We'll explore what that can look like in real life: not forcing yourself back to an old version of normal, but supporting your system as it searches for a new one, with as much gentleness, strategy, and companionship as possible.

Warmly,

P.S. If you know someone who is also navigating an ending or a transition, feel free to forward this and invite them to subscribe at andreanakayama.com. And if you’d like to share any of your own writing or reflections as we go, you’re welcome to hit “reply” or email me at scribe@andreanakayama.com

References:

Meleis, A. I. (2010). Transitions Theory: Middle-Range and Situation-Specific Theories in Nursing Research and Practice.

Meleis, A. I., Sawyer, L. M., Im, E.-O., Hilfinger Messias, D. K., & Schumacher, K. (2000). Experiencing transitions: An emerging middle-range theory. Advances in Nursing Science.

Meleis, A. I., & Trangenstein, P. A. (1994). Facilitating transitions: Redefinition of the nursing mission. Nursing Outlook.

Im, E.-O. (2011). Transitions theory: A trajectory of theoretical development in nursing. Nursing Outlook.

Schumacher, K. L., & Meleis, A. I. (1994). Transitions: A central concept in nursing.