Passage 4: Allostasis & Allostatic Load (when “holding it all together” becomes its own kind of wear and tear)

There’s a particular strangeness to this week on the calendar.

It’s late December—the days between one year and the next. Not quite holiday. Not quite “back to it.”

Calendars clear just enough for white space to appear. The inbox quiets down. Meetings fall away. The days blur a little. You might lose track of whether it’s Tuesday or Friday, but your body knows it has been through a year.

And even if you’re reading this at some other point in time, you likely know this feeling in other forms:

The week between a diagnosis and a treatment plan.

The gap between jobs, or roles, or relationships.

The stretch between a child leaving home and your life reshaping around the new quiet.

Light

Dark

Those are all “in-between” weeks too—when the outside world looks paused, but your inside world is working hard.

In a way, this whole series has been about that interior work.

In Passage 1, we explored endings—the quiet, inner “no more” that arrives before anyone else sees what’s shifting. In Passage 2, we examined rites of passage and liminal space, noticing how rare it is—especially in contemporary Western culture—to be formally held in the in-between. In Passage 3, we stood in the hallways of healthcare, recognizing that any shift in health is also a transition of care, whether or not the chart acknowledges it.

Here, in Passage 4, I want to turn our attention to something that’s been happening underneath all of that, all along: what your body has been doing, covertly and continuously, to keep you upright through all life’s transitions.

As this year winds down—or as you notice yourself in any season of “no longer / not yet”—you might be tempted to ask the usual questions:

How do I get back to normal?

What do I want my “new normal” to be?

But if we listen through a functional, biological, and narrative lens, a different set of questions emerges:

What work has my body done to keep me going, given everything that’s happened?

What kinds of adjustments—visible and invisible—has it been making on my behalf?

And what has been the cost of all that adaptation over time?

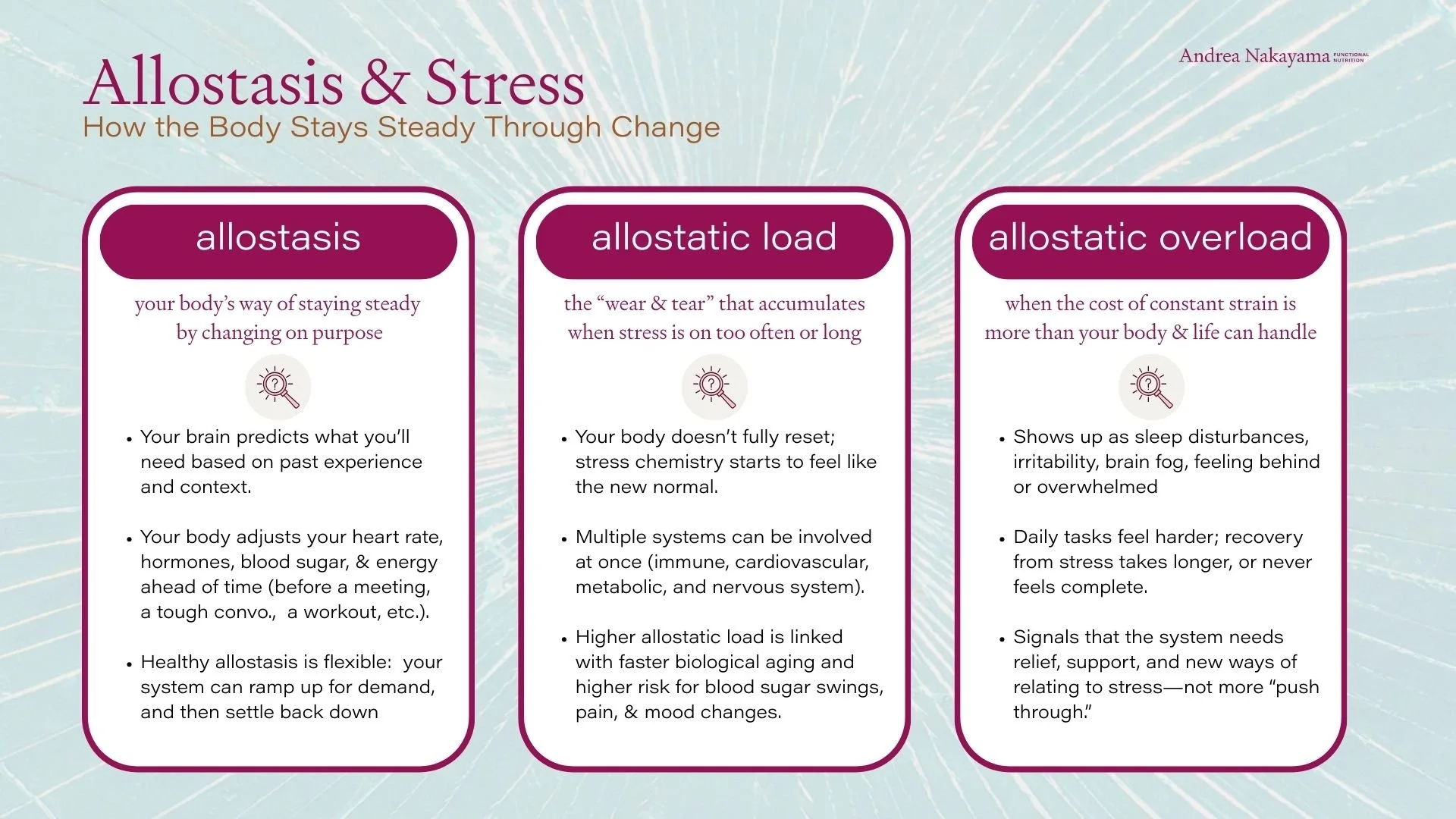

In the language of contemporary physiology, that’s the territory of allostasis. Allostasis isn’t just reacting. It’s forecasting—your brain predicting what you’ll need next and adjusting before the demand even arrives. Allostasis is often translated as “stability through change.” It’s your mind and physiology working together to keep you functioning in the middle of real-world stressors, not in a laboratory of controlled conditions.

Allostatic load is the other side of that coin: the cumulative “wear and tear” that builds when those adjustments are needed too much, too often, for too long—first in the body’s messengers (stress hormones and immune signals), and then downstream in sleep, blood sugar, mood, inflammation, and resilience.

In this Passage, and in whatever “in-between” you happen to be living, we’ll stay with that reality. We’ll honor the work your body has already done, and consider how you might move into the next chapter with a little less hidden cost.

The year my body raised a hand

There wasn’t a single dramatic collapse. No ambulance. No breakdown in the middle of a meeting.

It was more subtle than that.

It started showing up in the moments I used to pride myself on powering through: the seventh Zoom of the day—pivoting from teaching to leading to strategy to reporting on metrics, to podcast interviews—all without leaving the same chair. The color-blocked calendar with no buffers and another executive meeting around the corner.

It wasn’t just the volume—it was the relentless hat-switching between roles without the breathing room my schedule used to allow. Then there was the third strategy document open in too many tabs, each one making the same case I’d been building for two years: advocating for the mission, the vision, the values, the students’ needs I knew in my bones.

My voice could still do it. My slides could still hold the message. But my nervous system was paying interest. The output looked fine, but the internal cost didn’t.

One afternoon, I found myself searching. Not for a lost word, exactly, but for a new way to say what I’d already said, in every way I knew how. Usually, words are how I make sense of things. They’re my love language—how I lead, how I teach, how I connect. I’ve built an entire career on making the complicated legible—for patients, for practitioners, and for my team.

But that afternoon, the wires felt crossed.

The growing list of bullet points on the MacBook were technically okay. What I couldn’t access was the ease. It felt like I was wading through wet cement to form the next objective. The cursor blinked in the PowerPoint document, as if it was asking, "Again?"

My heart was doing the fast-but-not-quite-palpitating thing it had started to do in late mornings. Jaw tight. Shoulders climbing toward my ears. Eyes burning, even though I’d “only” been awake since 4:47 a.m.—another crack of dawn start, waking in the dark with thoughts galloping, sleep never finding its way back.

In reality, nothing significant had changed. I was still doing the work. I was still making sense. I would get the bullets written and delivered, and face the same challenge next week. From the outside, it probably looked like I was “handling it.”

But inside, the margin was gone.

“The output looked fine, but the internal cost didn’t.”

The effort it took to be patient, to say the same thing, yet another time, in a new way; to keep sounding clear and steady—that was what scared me. It wasn’t that I suddenly couldn’t do my job. It was that doing my job in the way that was required was starting to cost more than my body could handle.

It would’ve been easy to toss the overwhelm into one of the familiar piles: a busy season, midlife, tiredness, or even “just” another autoimmune flare.

None of that sort of blame was new to me. I’ve lived with Hashimoto’s for years. I’ve traveled through adrenal hyper-function, perimenopause, and menopause. I know what symptoms feel like. And I know what it is to track my own physiology and make intelligent adjustments.

But this didn’t feel like a sharp flare I could bounce back from with a few weeks of careful tending. My body’s internal settings had moved to a place where I could no longer pretend this was temporary

Less “off day,” more this is what functioning costs now.

The body that had been so willing to buffer each extra ask—one more monthly target, dissected into weekly increments that moved faster than the mission I kept trying to protect and uphold; one more meeting; one more late-night strategy push; one more early-morning catch-up on the tasks that didn’t fit anywhere else—was starting to hand me the receipts.

And this is where I want to be careful with the story. Because in a culture that loves personal responsibility, it’s easy to turn a moment like this into self-indictment: I didn’t manage my stress well enough. I should have optimized sooner. I should have had better boundaries. I should have spoken up.

The truth is, I was doing many of those things. But through the lens of allostasis, that’s not the most accurate frame. And like any system asked to accommodate too much, too often, for too long, my body was beginning to let me know.

“My body wasn’t failing. It was adapting—and handing me the receipts. In a resourced system, the stress response turns on—and then turns off. This year, “off” started to feel harder to reach.”

A week later, my labs caught up to what my body was already telling me. Thyroid markers shifting from their baseline. Inflammatory tone a little higher than my usual standard. Nothing catastrophic. Just enough to confirm that my body wasn’t just being difficult. It was responding to the year I’d had. Appropriately raising a hand.

In my mind, I was still justifying: It’s a big season. I’ll handle it. I need a better system, a tighter calendar, one more walk, a more dialed-in supplement protocol.

In hindsight, through the lens of allostasis, something else was happening.

My brain had been adjusting the dials for a long time—nudging cortisol and adrenaline to get me through one more set of steep goals, tightening blood pressure and vigilance for one more high-stakes conversation, asking my thyroid and immune system to keep recouping so I could stay “on” for the next meeting, the next crisis, the next late-night spreadsheet analysis. None of those things is why I do what I do—and yet all of them were my whole-body attempt to safeguard what matters.

My body was conforming to all the pressure I asked it to endure, and like any system asked to adapt too much, too often, for too long, it was starting to show the cost.

Around this point, I found myself thinking of that now-famous phrase from psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk: "The body keeps the score." Not as a trauma statement (not yet), but as a simple reminder: the body is an honest bookkeeper. It doesn’t argue with the calendar or the narrative I tell myself. It just records. And as van der Kolk writes, healing begins when we “become familiar with and befriend the sensations in [our] bodies.”

In allostatic terms, that’s the pivot: learning to read the score before the body’s adaptive range narrows—before the receipts become a bill.

That’s the juncture I want to explore with you here—not as a confession, but as a case study: how a body that looks “fine” from the outside can be carrying an invisible strain for years of doing what life, work, and love have asked of it.

““Our bodies are the texts that carry the memories and therefore remembering is no less than reincarnation.””

Homeostasis vs. allostasis

If homeostasis is the body’s impulse to keep things “steady,” allostasis is the system’s ability to keep you alive and functioning when steady isn’t an option.

Allostasis was coined to name something physiology has always been doing, even when we didn’t have language for it: the body doesn’t just restore balance—it creates it, again and again, in the middle of shifting demands. The term is most often traced to the late-1980s work of Peter Sterling (a neuroscientist/physiologist) and Joseph Eyer (a health researcher who helped frame the idea in a broader, real-world context).

Once you see it, you start to notice it everywhere. Resilience isn’t just “being strong.” It’s having enough slack to bend—and enough recovery to return. A bridge isn’t built to be rigid. It’s built to flex. Wind, weight, vibration—there’s designed movement in the architecture. The problem isn’t that it moves. The problem is when the load keeps coming, and the structure never gets a break—when flex becomes fatigue. A rubber band can stretch far beyond its resting shape and still return. That’s the miracle. But hold it taught for too long and it loses its elasticity, or snaps—one dramatic moment. That laxity is one of the simplest ways to understand allostatic load.

And your body isn’t responding only to the stretch, pull, and strain right now. It’s responding to what it predicts will happen next—shaped by what it has already lived through. It doesn’t wait until the meeting starts to raise your heart rate. It doesn’t wait for the flight to land to swell your ankles. It doesn’t wait for the conflict to arrive to tighten your jaw. It prepares. It braces. It compensates. It tries to keep you upright in real life.

That’s the generosity of allostasis.

It’s the body’s “adjustment team,” running in the background

And allostasis isn’t one system. It’s a coordinated response across many systems. First, the messengers change—stress hormones and immune signals. Then the downstream systems start paying: sleep, blood sugar, mood, inflammation, blood pressure, bandwidth.

It’s your brain acting like an air-traffic controller—tracking inputs, predicting what’s next, and directing multiple systems to adjust in real time. It’s integrating sensory input, memory, meaning, and frame of reference. And here’s the part that matters in the context of “load”: Allostasis is not only activated by danger. It’s activated by demand.

Not just a predator, but a deadline.

Not just injury, but responsibility.

Not just a crisis, but sustained output without sustained recovery.

““Homeostasis is reactive; it waits for a variable to deviate before initiating a corrective response. Allostasis, by contrast, is predictive; it adjusts parameters before the disturbance occurs.””

Real-world examples (the kind that actually live in your body)

I realize it can help to make these concepts concrete within your own body, with the familiar moments your own life may dish up to keep you balanced in the face of destabilizing factors. Let’s consider some of those allostatic mechanisms working for you… even right now.

1) Your liver as backup generator

The liver is one of your body’s leading fuel managers. When you wake early, move straight into cognitive work, prolong time between meals, or run on coffee for momentum, your liver doesn’t object right away. It compensates—releasing stored glucose (glycogen) or making new glucose (gluconeogenesis) to keep your brain fueled. (And if you’re intentionally keto-adapted or fasting on purpose, the fuel mix may shift—but the liver is still part of the relay). In a short burst, these internal mechanisms are part of your body’s brilliance. But over time, you’ll feel the toll. It’s like running a backup generator every day because the power grid isn’t stable.

2) Your immune system as nimble negotiator

If you’re sleeping lightly, traveling, or under-resourcing recovery, taking in inputs your full body system can’t comfortably process right now—through food, through air, through skin—or carrying emotional strain, your immune system doesn’t simply switch “off.” It recalibrates. Sometimes it dampens sickness signals in the short term—less fever, less fatigue, less body-ache “shutdown”—so you can keep functioning. Sometimes it does the opposite and raises baseline inflammatory tone because the system is on alert. And sometimes it does both in overlapping ways—which is one reason people can feel simultaneously wired and tired. Over time, for some bodies—especially those already prone to inflammatory or autoimmune patterns—those recalibrations can start to feel less like flexibility and more like a highly sensitive system.

3) Your nervous system as executive assistant

Before you speak, your body prepares you to be persuasive. I’m not being polite or poetic—that’s physiology at play. Your heart rate rises slightly, your breathing changes, your attention narrows, and your muscles hold you in a more “ready” posture. Again: useful. But if you do this five, six, seven times a day—day after day—without true downshifting (think: sleep, relaxation, breathwork, love, joy, nature, movement), the cost doesn’t always show up as a breakdown. Instead, it shows up as less leeway.

4) “Good stress” still counts

There are reasons and seasons when the demands are meaningful: building, leading, caring, teaching, advocating, parenting, grieving, managing change. Even when the mission is internally aligned, you physiologically still have to finance the effort. A body can love the purpose and the cause and still struggle with the pace and insistence.

““To maintain stability an organism must vary all the parameters of its internal milieu and match them appropriately to environmental demands.” ”

So where does allostatic load come in?

Allostatic load was a concept articulated in the early 1990s by Bruce McEwen, a neuroendocrinologist who studied how stress mediators shape the brain and body, and Eliot Stellar, a psychologist known for linking brain, behavior, and physiology. Their contribution was to name the accumulated cost of adaptation over time: the “price of staying functional” when the system has to adjust too much, too often, for too long.

What matters most here is that load isn’t proof you’re doing life wrong. It’s often proof you’ve been doing life faithfully—showing up, holding things together, staying productive, staying useful, staying “fine.”

“Allostatic load is not a moral failure. It’s a biological reckoning.”

Allostatic load builds when:

the stress response is activated repeatedly with insufficient completion or recovery

the body has to keep overriding signals (hunger, fatigue, emotion, pain, intuition) to meet external demand

the conditions are prolonged or chronic (not acute), and the system starts treating “elevated output” as the default setting

the story on the outside stays functional, while the inside spends more and more to maintain that appearance

Quiet signs the buffer is gone

Allostatic load rarely announces itself with a siren. More often, it shows up as that loss of margin—the small costs you didn’t use to have to pay. In my work, signs of the load increasing might be the clenched jaw, scrunched shoulders, early waking, “fast-but-not-quite-palpitating” heart. The loss of ease. The sense that clarity now costs more.

Those are not always “a flare” in the alarming, clinical sense. Sometimes they’re the body whispering:

I can do this.

I have been doing this.

But I can’t keep doing it at this rate without it impacting me or costing me something else.

Which is why allostasis is such a compassionate lens: it doesn’t begin with “What’s wrong with you?” It begins with: What has your system been asked to carry—and how has it kept you going?

““The allostatic system may stay on for a bit too long—the orchestra of chemical mediators keeps playing an encore.””

The social story: how our lives keep resetting “normal”

One of the reasons allostasis is so empathetic is that it doesn’t pretend your body is adapting in a vacuum. It’s reorganizing inside a culture that keeps moving the goalposts. “Normal” used to imply a rhythm—effort, and then recovery—a season of push, and then a season of repair. But for many of us, “normal” now looks more like a series of rolling reboots: just as you regain your footing, the terrain shifts again, asking for more.

Sometimes the appeals are barely nameable:

a new platform, a new system, a new expectation

a calendar that fills itself faster than you can protect it

news cycles that keep your attention on alert

relationships stretched thin by distance, stress, or unspoken grief

the background hum of “keeping up,” even when nothing is technically wrong

And then there’s the ambition that doesn’t appear on any agenda except your own: The internal audit. The comparison. The quiet self-correction that never clocks out. Nothing is “happening,” and yet your system stays subtly engaged—because you’re measuring yourself against someone else’s output, or your own impossible standard.

It’s worth saying that kind of drive didn’t arrive out of nowhere. For a lot of us, it began as a perfectly reasonable developmental strategy. In young adulthood, you need a little stress chemistry. You need momentum. You need the physiological “yes” that gets you moving—out of inertia, out of doubt, out of the fog of adolescence and into your own life. You learn what your body can do. You lift heavier weights. You take the early shift. You stay up late finishing the paper. You push through the awkward middle of becoming.

And it works, which is why it’s so seductive.

Your system learns the pattern: catalyze → perform → succeed → repeat.

The body absorbs that training.

So when life gets bigger—more roles, more responsibility, more pressure, more people depending on you—the same strategy that once helped you launch can take over. The nervous system stays rallied as a baseline. The “off switch” becomes less accessible. Rest starts to feel unproductive. Stillness starts to feel unsafe. Even joy can come with a slight edge of urgency: don’t waste it, don’t lose momentum.

For women, there’s an added layer: we’re often rewarded for overriding ourselves. The body can meet that standard for a while—through allostasis, through adaptation—but the cost shows up eventually as allostatic load: the slow accumulation that happens when “push” outpaces “recover.” And when the baseline is chronic demand, we tend to treat habitual adaptation as a personality trait rather than a biological process.

What begins as drive can become a default. And for many women, that default doesn’t stay personal for long—it gets rewarded, expected, reinforced.

The contract

For many women, “busy” isn’t just a stretch of time. It’s a social contract.

It’s not because we don’t want rest, but because somewhere along the way, worth got coupled to capacity. To being the one who remembers, the one who anticipates, the one who holds the emotional temperature in a room and still gets the work done.

We’ve added roles without retiring any, and we’ve rewired our identity endurance as evidence of worth.

More access. More opportunity. More responsibility. More visibility. More leadership. More caretaking. More data. More decisions. More self-management.

“For many women, “busy” isn’t just a stretch of time. It’s a social contract.”

And while some of that expansion has been hard-won and meaningful, the body doesn’t sort “chosen” stress from “imposed” stress the way our ideals do. It just registers the requirements. So even when there’s no single crisis, the load builds through accumulation:

the job that travels home in your pocket (or pocketbook)

the family logistics that live in your head

the relational labor you do because someone has to

the diligence that comes from being a woman in a world that still asks you to be both pleasing and powerful—sometimes in the same sentence

And yes—men are carrying more, too.

Many are navigating their own impossible standards: performance, provider pressure, disconnection, the expectation to be steady and self-sufficient even when depleted. And yet culturally, women are still more likely to be assigned the “invisible” work: the remembering, the soothing, the tracking, the caring, the emotional continuity. The work that doesn’t get a line item, but absolutely draws on the nervous system. Which means “everyone’s busy” can be true—and still hide an unequal distribution of load.

Of course, the “load” of social contracts doesn’t land evenly. It’s shaped by culture, class, race, disability, migration stories, chronic illness, neurodiversity, and the unspoken rules of whatever rooms you move through. Gender is part of the story—but not the only axis.

Scope creep

Now add to that the modern work container—constantly reshaping what “normal” asks of us. Not just more work, but wider work.

In many roles the expectation isn’t depth or breadth. It’s both.

Be strategic and responsive. Creative and measurable. Lead and execute. Hold the mission and hit the metric. And do it fast—often in fragments—before the next meeting starts. (Deloitte’s human capital work describes this “boundaryless” tension as a defining feature of performance in today’s workplaces.)

And this is where biology stops being metaphor.

Because constant hat-switching isn’t only a productivity issue—it’s a regulation issue. Each context shift is a tiny reorientation: different stakes, different audience, different tone, different “version of you.” Useful in short bursts, but costly as a baseline.

And the modern workday has an additional trick: it rarely gives the body a clean ending. It doesn’t resolve into “done” so much as dissolve into one more message, one more dashboard check, one more “quick thing” or Slack “ping.” Work doesn’t stop. It fades—while your system stays partly online.

Which means your body doesn’t reliably get the message: you’re safe to stop now.

The moving goalpost

The fundamental shift isn’t just that life got fuller. It’s that the baseline moved—and keeps moving: faster response times, higher output, more availability, more self-optimization, more performative competence.

And under persistent pressure, habituation starts to look like identity:

She’s so on top of it.

She’s so capable.

She’s so resilient.

But resilience isn’t an identity either. It’s a biological process—and it requires recovery. If nothing ever comes off the plate, the plate doesn’t get stronger. It just gets heavier.

This is where allostatic load becomes a lived experience. Because your body isn’t only responding to what’s happening inside you—it’s responding to the conditions around you: the pace, the instability, the relentless switching, the requirement to perform calmly while managing pressure.

And there’s a particular strain in the in-between seasons—the ones we don’t formally honor. We have language for those big moments: birth, death, marriage, illness, divorce, retirement. But we have far less language for the long middle stretches:

caregiving that doesn’t end

projects that never quite complete

deadlines on constant repeat

rebuilding after a loss that isn’t visible

learning your body again after a transition

a role that expands while resources stay the same

the daily labor of being the stable one

These all require adaptation.

And because they’re not always named, they’re often not supported.

So we cope. We compensate. We create “normal” inside the new conditions. Sometimes that looks like resilience. Sometimes it looks like high functioning. Sometimes it looks like being praised for how much you can carry. But physiologically, it’s just more sustained adjustment. Not because you’re fragile, but because you’re human—living in relationship with a world that keeps changing.

So maybe the question isn’t “Why am I tired?” or “What’s wrong with me?”

Maybe it’s:

What have I been treating as usual that my body has been privately working overtime to sustain?

What has become ask-after-ask, without the kind of completion that lets the nervous system truly downshift?

Where have I been living as if recovery is optional—when recovery is part of the design?

If allostasis is the body’s generosity—stability through change—then the social story matters because it tells us how much change we’ve been living inside of. And when “normal” keeps resetting, the work of acclimating becomes invisible—not only to other people, but to ourselves as well.

Until the body raises a hand.

Not to accuse, or punish. But to report. To say: I can keep doing this. I have been doing this. But the cost is rising.

And that’s not a personal failure, a crime, or an action that should elicit punishment. It’s a signal worth listening to—especially in the less taxing times, when the world quiets down just enough for your body’s truth to become audible.

The body as historian

Allostatic load isn’t a single symptom. It’s a whole-body pattern—a body that’s been compensating across hormones, immunity, metabolism, and nervous system tone—until compensation starts to feel like the new baseline. That said, it may appear as one symptom or diagnosis, representing the tipping point of the burden the body has been bearing.

One way to hold this without getting lost in the physiology is a simple metaphor that shows up often in stress-and-health conversations: a bucket. Not because the body is simple like a bucket, but because the bucket helps us see what real life tries to hide: Everything is connected. And everything counts.

Inflammation changes hormone signaling. Hormone shifts change sleep. Sleep changes blood sugar. Blood sugar changes immune response. The nervous system tone changes digestion. Digestion changes inflammation.

“Symptoms are often the downstream story the body tells when upstream strain has gone unnamed for too long.”

The systems don’t take turns. They co-regulate.

One reason the bucket metaphor is useful is that it helps explain why symptoms can feel sudden even when the burden has been building for a long time.

Sometimes the “spill” looks like it came out of nowhere—when really, it’s the waterline finally crossing a threshold.

A reactivity event. The trigger is real—and so is the context: thin sleep, viral recovery, alcohol, high nervous-system arousal, baseline inflammation. One more pour, and the system overflows.

A hormone flare. Not random—often downstream of upstream strain: sleep disruption, blood sugar volatility, chronic inflammation, under-recovery. Hormones don’t misbehave in isolation; they try to regulate inside whatever terrain they’re given.

A mental health “moment”. Anxiety, irritability, low mood, brain fog—sometimes these are the mind’s experience of a whole-body state: swinging blood sugar, fractured sleep, elevated inflammatory tone, a nervous system that can’t fully downshift.

And of course, any severe allergic reaction, chest pain, fainting, or thoughts of self-harm are urgent. If that’s you, please don’t read the rest of this alone—get support right away.

The bucket represents your body’s shared capacity to hold its hardships, past and present. Now imagine multiple faucets pouring into that one bucket, all day long, year after year… and one shared drain at the base of the bucket.

The faucets

Some inputs are obvious: deadlines, caregiving, conflict, travel, illness, accidents, grief. Others are understated, harder to name, but just as real to the full body system: the internal audit, the comparison, the half-finished workday, the constant hat-switching, the background hum of “I should be able to handle this.”

And here’s the important part: the bucket doesn’t only fill with what’s “bad.” It fills with what’s demanding—even the meaningful or purposeful demand.

The drain

The drain is recovery—sleep, relaxation, nourishment, hydration, movement, connection, breath, stillness, laughter, time outside… the moments where your physiology gets the message: We’re safe enough to stop bracing.

When the drain is open, and the inflow is reasonable, the bucket fills… empties… and fills and empties again. That’s a healthy rhythm.

And this is where it helps to introduce a word that gets tossed around a lot in longevity circles: hormesis.

Hormesis is the body’s capacity to respond to a small, time-limited stressor by becoming more resilient afterward. It’s the sunny side of stress—stress that arrives in a dose the body can handle, with enough recovery on the other side to integrate the benefit.

In that kind of balanced system, certain “stress practices” can actually support the drain:

a short fast that gives the digestive system a break and signals metabolic flexibility

a cold plunge that briefly mobilizes you, then settles into a deeper downshift afterward

heat exposure (sauna) that feels like a challenge, then leaves you calmer and clearer

power lifting that creates micro-demand, then builds capacity in recovery

even phytochemicals in bitter plants and colorful foods—tiny signals that invite repair pathways online

Hormesis only works when the body has room to respond—and room to recover.

Which means that these same practices can yield very different results when the contents of the bucket are already high. Because in a burdened system, those “good stressors” don’t always read as training signals. They can read as more inflow—and sometimes even a narrowing of the drain.

A few real-life examples:

If sleep is already thin, blood sugar is unstable, and cortisol is already elevated, fasting may not feel clarifying—it may feel like more bracing.

If your nervous system is already living in high alert, cold exposure may not build resilience—it may reinforce mobilization.

If inflammation is already loud, intense workouts may not feel strengthening—they may feel like a longer recovery debt.

If you’re running on borrowed adrenaline, adding more “challenge” can quietly keep the system from ever getting the message: we’re safe now.

That’s the nuance most health and longevity hacks leave out: the benefit depends on baseline load.

A hormetic input is only hormetic when it’s paired with an open drain.

As I often say, you cannot use the tools of optimization for stabilization.

So the question isn’t “Is fasting/cold/heat/exercise good or bad?” It’s:

Is my system currently resourced enough to treat this as a signal—and not a threat?

Does this practice widen my drain afterward… or does it leave me more wired, more brittle, more depleted?

Am I training resilience… or rehearsing strain?

In allostatic terms, hormesis is stress that completes. Allostatic load occurs when stress stacks—especially when recovery can’t keep up.

And that’s why the drain matters as much as the faucets.

What counts as load

In real physiology, the “water level” in the bucket isn’t one thing. It’s a shared load moving through interconnected systems—multiple inputs, one body.

Here are some of the main streams that can contribute to that level:

Immune/inflammatory load

Readiness, repair, defense, and the background alertness the immune system maintains when it is strained. This is where things like viral burden (a recent infection, post-viral recovery, frequent “almost getting sick”), ongoing antigen exposure, and baseline inflammation can steadily raise the waterline.Histamine/reactivity load

For some bodies, the bucket includes a strong “reactivity” faucet: histamine tone, mast-cell signaling, seasonal flares, food or environmental triggers. It’s not because you’re doing something wrong—it’s because your system is responding to what it reads as too much.Hormone load

HPA-axis stress signaling (cortisol/adrenaline), thyroid signaling, insulin and blood sugar regulation, sex-hormone shifts and rhythms. This is where the bucket can surge during perimenopause/menopause, thyroid vulnerability, blood sugar volatility, or times where the body is leaning hard on stress hormones for momentum.Nervous system load

Arousal, threat detection, recovery capacity, vagal tone—how often you mobilize, and how fully you return. This includes the cost of constant context-switching, sustained vigilance, and living “on-call”—where you can be contacted at any time (text, Slack, email, “quick-question”).Metabolic/energy load

Fuel availability, mitochondrial output, blood sugar stability, insulin productivity—how hard the body is working to keep energy online. You can feel this as crashes, wired-tired energy, needing more caffeine, sugar, or carbs than you used to, or the sense that output costs more.Hydration/mineral load

Not just “drink more water,” but whether your body can actually hold hydration: electrolytes, sodium/potassium balance, fluid shifts, the way stress hormones change thirst and urination. When hydration is off, it can amplify heart flutters, headaches, fatigue, and even histamine reactivity in some people.Clearance/processing load

Liver processing, bile flow, elimination, lymph—how effectively “spent” materials and inflammatory byproducts move out of your body. This is also where people may notice sensitivity to alcohol, fragrance, cleaning products, smoke, moldy environments, or just a sense of “my system can’t handle what it used to.”Brain load

Attention, language, memory, emotional regulation, decision fatigue—the cost of staying coherent and steady. This is the “too many tabs” part of the bucket: not weakness, but bandwidth.

The point isn’t to turn your body into a problem list. It’s to name what’s often invisible: the bucket can be high for myriad reasons at once, and the body experiences the sum, not the labels. It also gives us ways to get personal and explain why two people can live the same week and have very different physiological receipts.

Everything is connected. We are all unique. All things matter.

Why the bucket stays high

The trouble isn’t just the water flowing in. It’s that the drain can narrow at the same time, often for physiological reasons: sleep disruption, hormonal transitions, inflammation, nutrient depletion, loneliness, lack of safety, a day with no proper ending, a body that never gets the signal we’re done now.

So you can be doing many of the “right” things and still feel like the bucket won’t empty—because your system is budgeting inside overload. Again, not one factor, but an accumulation of many.

The body’s workaround

The chronic strains of life are where allostasis is so benevolent and beneficial. Under constant demand, the body is wise about rerouting:

If sleep is light, it leans harder on stress hormones for momentum.

If immune tone is elevated, thyroid signaling may falter.

If blood sugar is unstable, the nervous system stays more reactive.

If the nervous system never truly downshifts, digestion and repair don’t get fully funded.

That’s not weakness. It’s strategy.

(Some people call this homeostasis, but in Functional Medicine we tend to think of it as a homeodynamic system—flexible, pliable, constantly recalibrating. Our bodies are designed to adapt and function as best as they possibly can for us. Until they can’t.)

A few questions worth asking

The bucket metaphor isn’t meant to flatten the body’s complexity. It’s intended to make the complexity trackable—so you can see accumulation sooner, with less self-blame. Whether or not we pay attention, your body is already taking notes, not in sentences, but in signals.

In how quickly your jaw tightens.

In how shallow your breath gets without you noticing.

In the hour you wake—again.

In the way certain tasks require more “startup cost” than they used to.

In the way your patience thins, or your appetite shifts, or your heart runs a little ahead of you.

You don’t have to become hypervigilant to be wise. You just have to become a compassionate observer—your own steady chronicler.

So here are a few questions to consider—not as a checklist, but as a way of listening for load:

What’s filling my body’s bucket right now—both the obvious and the unnamed? The obvious might be deadlines, caregiving, money stress, travel, grief, health concerns, or an unrelenting season of change. The unnamed might be the running mental tab of what I’m forgetting, the low-grade dread before opening my inbox, the comparison spiral, the self-critique, the way I stay half-reachable even when the day is technically over.

What narrows my drain, even when I’m “doing the right things”? Not just what I do, but what constricts recovery: fragmented sleep, inflammation, hormones shifting, loneliness, blood sugar volatility, context-switching, a day with no clean ending, a nervous system that never gets the memo that we’re safe to stop.

Where have I been asking my system to stay online without completion? Where does effort dissolve instead of ending—one more check, one more message, one more “quick thing”—while my biology keeps bracing as if it’s not allowed to power down?

What have I been calling “normal”—and what is it costing my body to maintain that story? Normal might look like answering messages while making dinner, sleeping with my phone close enough to hear it, treating a 10 p.m. second wind like productivity, running on coffee until I can get to a real meal, stacking meetings without buffers. And the cost might show up as shallow breathing I don’t notice until I sigh, sleep that doesn’t restore, digestion that slows or flares, a shorter fuse, more reactivity, or that creeping sense that everything requires more startup cost than it used to.

The goal is to recognize that you are a human being, in a human body, and to notice the rising waterline early enough—gently enough—that your body doesn’t have to raise its hand just to be heard. Not because you’ve failed, but because you’re finally listening to the part of you that has been faithfully keeping the record.

And here’s the gift of the liminal week: it’s one of the few stretches of modern life where the outside world quiets down just enough to hear the inside world. Not perfectly. Not magically. But just enough. Enough to notice what the body has been holding. Enough to offer it a clean ending. Enough to practice a different rhythm—before the next year asks you to gear up again.

From historian to steward

There’s a moment I’ve noticed in myself—maybe you’ll recognize it too.

It usually happens in the evening, when the day is technically “over,” but my body hasn’t received the memo.

The laptop is closed, but my jaw is still holding. Dinner is on the table, but my mind is still scanning. The room is quiet, but something in me is still listening—on alert for the next ping, the next need, the next thing I forgot.

And what surprises me is how little it takes to tip the system.

A podcast that carries a little edge. A show that’s not even scary, just charged. A minor disagreement with my boyfriend. A message that reads, “We need this now.”

My physiology responds as if something important is happening—even when the content is objectively small. That’s the thing about allostatic load: when the baseline is already elevated, the body treats tiny signals like they matter more than they should. The stress response mobilizes quickly… and then it doesn’t resolve cleanly. The day is technically over, but internally, there’s no clear ending. The cortisol queen is off to the races—and I’m left trying to coax my system back down with logic, when what it needs is completion.

And this is where allostasis can feel almost haunting in its competence. Because the body doesn’t just respond to what’s happening, it responds to what might happen. It keeps a running forecast. It prepares you. It steadies you. It keeps you functional.

Until “functional” becomes the only mode your system recognizes.

So before we move into any antidote or action, I want to say this plainly:

If you’ve been living in a body that’s constantly adjusting, you don’t need a new personality. You don’t need more grit. You don’t need a better morning routine as proof of worth.

You need more completion.

Not completion as in “everything is done.” It may never be. Completion as in: your physiology gets a clear signal that the effort is over. At least for now.

And that’s where the simplest allostatic practice begins—not with more doing, but with a different kind of seeing.

A simple practice: many faucets and a drain

If the bucket metaphor helps at all, it does here: multiple faucets feed into a shared bucket. One drain empties it.

So when the waterline is high, you only ever have two options:

reduce inflow (turn down a faucet or two), or

widen outflow (open or clear the drain).

Most of us try other things instead. We hold our breath and carry the bucket faster. We try to address multiple faucets at once without considering the drain. We focus on the drips that are contributing while not looking at the primary channel.

But biology is not impressed by most of those tactics.

Here’s a practice you can do in a few minutes—once, or daily, or only in this liminal week. It’s not a protocol. It’s a way of listening that tends to generate surprisingly practical answers.

Step 1: Name the loud faucets

Without editing, write down what’s clearly pouring in right now. Not forever—just now.

Deadlines. Caregiving. Money stress. A relationship strain. Travel. Health concerns. A difficult decision. Grief that hasn’t had space to metabolize. An ending that hurts or hasn’t gone the way you expected.

Don’t problem-solve—just name.

Step 2: Name the quiet faucets

Now name what doesn’t show up on your calendar but still draws from your system:

The self-criticism. The comparison. The constant context-switching. The “I should be able to handle this.” The way you stay slightly reachable, slightly ready, slightly on-call. Never unplugging.

Step 3: Ask one honest question

Not: What should I do?

But: What faucet can I turn down by 10% this week?

Not 100%. Just 10%.

That might look like:

no “quick thing” after dinner

fewer tabs (one task window before you switch)

one fewer hard workout if recovery has been thin

less alcohol/sugar if you already know it spikes the bucket

pausing the late-night research spiral

declining one thing that is optional but draining

The point is not discipline or perfection. No gold star. This is self stewardship.

Step 4: Open the drain—on purpose

Now ask: What widens the drain for me by 10% this week?

Sleep is the obvious one, but it’s not the only one. Recovery isn’t only rest—it’s regulation. In my approach, I’ve always thought of sleep, elimination, and blood sugar balance as the Non-Negotiable Trifecta. All these factors open the drain.

Other drain-openers might be:

a genuine downshift before bed (not scrolling, not “just finishing”)

daylight + a walk to reset circadian rhythm and nervous system tone

protein, fat, fiber, and hydration early enough to stabilize blood sugar

warmth (bath, shower, tea) as a safety cue

laughter, touch, music, nature—things that tell the body, we’re not under threat right now

connection that soothes (not connection that performs)

Here’s the key: You don’t open the drain by adding more effort or willpower. You open the drain by giving your body a message it believes—one that conveys safety, and with signals your nervous system trusts: rhythm, warmth, exhale, presence, a clean ending. And what your body trusts is shaped by what it has lived through and what it’s carrying right now—not just by the “objective” facts of the moment. Safety and trust are very unique experiences.

Self-advocacy, reframed

Self-advocacy is often described as speaking up. In an allostatic frame, it’s also something refined: Protecting the drain. Turning down the faucets. Telling the truth about your capacity.

Remember: the body can do almost anything for a while. But “for a while” isn’t a strategy.

So here are a few sentences you can borrow as concepts to try on that let your body stay honest:

“I can do that, but not at that pace.”

“I’m protecting recovery right now.”

“I’m not available for after-hours decisions.”

“Let me answer tomorrow—my system is offline tonight.”

“I need a clean ending today so I can show up tomorrow.”

You don’t have to justify your biology. You can simply honor it.

Stability through change

This series is about transition—about the seasons of change we rarely ritualize. And allostasis gives us one of the most tender interpretations of what it means to live through change:

Your body is not weak because it needs to adjust.

Your body is wise because it knows how.

“Stability through change” doesn’t mean staying the same. It means changing in a way your system can afford. And allostatic load doesn’t mean you’ve done life wrong. It often means you’ve done life with devotion: showing up, holding things together, staying useful, staying fine.

Until fine costs too much.

So if your body has raised a hand, try not to turn it into an accusation. Instead treat it as what it is: A report. A record. A kind of intelligent honesty.

Not to shame you. To guide you.

Because when the world quiets down—whether it’s late December, or the week between diagnosis and plan, or the gap between who you were and who you’re becoming—your body is still here, doing what it has always done: keeping you upright.

And right now, maybe it’s inviting you to do what you can to make uprightness cost a little less.

Late December doesn’t fix anything. It doesn’t erase the year you’ve just lived. But it sometimes does something rare: it lowers the volume of the outside world enough for your inside world to come back into focus.

If you can, let this week be less about “getting ready” and more about giving your system a clean ending. A few signals that say: we’re not bracing right now. Because the point of stability through change isn’t to become unshakeable, it’s to become recoverable. And if your body has raised a hand this year like mine has, maybe this is the moment to meet it.

When the calendar flips, the world will ask again.

But you’ll be answering from a body that feels a little more like home.

There are 8 Passages in this series. You’ll find the next Passage 5: The Window of Tolerance here.

Warmly,

P.S. If you know someone who is also navigating an ending or a transition, feel free to forward this and invite them to subscribe at andreanakayama.com. And if you’d like to share any of your own writing or reflections as we go, you’re welcome to hit “reply” or email me at scribe@andreanakayama.com

References:

Sterling, P., & Eyer, J. (1988). Allostasis: A new paradigm to explain arousal pathology. In Handbook of Life Stress, Cognition and Health.

McEwen, B. S., & Stellar, E. (1993). Stress and the individual: Mechanisms leading to disease. Archives of Internal Medicine.

Seeman, T. E., McEwen, B. S., Rowe, J. W., & Singer, B. H. (2001). Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Deloitte Insights. (2024). 2024 Global Human Capital Trends: Thriving beyond boundaries: Human performance in a boundaryless world. https://www.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/articles/2024/glob176836_global-human-capital-trends-2024/DI_Global-Human-Capital-Trends-2024.pdf

DeVita-Raeburn, E. (2018, October 16). Bruce McEwen, PhD: Q&A on Your Body on Stress. Everyday Health. https://www.everydayhealth.com/wellness/united-states-of-stress/advisory-board/bruce-mcewen-phd-q-a/